[This is a note, which is the seed of an idea and something I’ve written quickly, as opposed to articles that I’ve optimized for readability and transmission of ideas.]

$$

\newcommand{\mb}{\mathbb}

\newcommand{\mc}{\mathcal}

\newcommand{\E}{\mb{E}}

\newcommand{\B}{\mb{B}}

\newcommand{\kl}[2]{D_{KL}\left(#1\ \| \ #2\right)}

\newcommand{\argmin}[1]{\underset{#1}{\mathrm{argmin}}\ }

\newcommand{\abs}[1]{\left\lvert#1\right\rvert}

\newcommand{\atup}[1]{\left\langle#1\right\rangle}

\newcommand{\set}[1]{\left\{#1\right\}}

\newcommand{\t}{\theta}

\newcommand{\T}{\Theta}

\newcommand{\p}{\phi}

$$

Related notes:

- Active inference tutorial (actions)

- Hackmd version of this note: https://hackmd.io/@z5RLVXyrTg-JLCnL9c_xOQ/r1KSFUjkO

My current understanding

Note on probability notation

These are my informal notes. Probability notation can be cumbersome and overly verbose. As is customary in machine learning and many of the sciences, I’m not going to bother using probability notation correctly. That is to say, I’m going to mangle and confuse probability measures, random variables, and probability mass/density functions. Hopefully readers can figure out the intended meaning of my notation from context, and I try to clarify when needed.

In general, figuring out good notational conventions for probability in many fields (I’m looking at you machine learning, but the neuroscience free energy literature also has this problem) seems to be an unsolved problem, and one that I’d like to work on at some point! However that is not my concern here. I’m just taking the easiest route to expressing my knowledge. If you want to know what “proper” probability notation looks like, check out my post on probability theory.

Bayesian basics

Suppose $\mc{H}$ is a set of possible hidden states, and $\mc{X}$ is a set of possible observations. Each $h\in\mc{H}$ explains data $x\in\mc{X}$ through the conditional data distribution $p_{X \mid H}(x \mid h)$, or also notated $p_{X \mid H=h}(x)$. A Bayesian mixture is the mixture distribution

$$

p_{X,H}(x,h) = p_H(h)\cdot p_{X \mid H}(x \mid h)\,,

$$

where $p_H(h)$ is called the prior. We can then compute the posterior $p_{H \mid X}(h\mid x)$. The marginal distribution $p_X$ is called the subjective data distribution, since it is partly determined by the choice of prior (if we assume the prior is subjective, i.e. quantifies personal belief). $p_X$ is an agent’s best prediction for what they will observe given what they believe (the prior).

The philosophy of Bayesian information

There are different ways to interpret quantity of information information. In the Bayesian setting, I like to think about the amount by which a possibility space was narrowed down. A probability $p_X(x)$ on $x\in\mc{X}$ represents the fraction of possibilities that remain after observing $x$. If we suppose there is a finite possibility space $\Omega$, and the function $X : \Omega \to \mc{X}$ is a random variable that tells us “which $x$” a given $\omega\in\Omega$ encodes, then the probability of $x$ is

$$

p_X(x) = \frac{\abs{\set{\omega\in\Omega : X(\omega) = x}}}{\abs{\Omega}}\,,

$$

which is the number of $\omega$s that encode $x$ over the total number of possibilities. This setup is supposing that $x$ is a partial observation, meaning that even after observing $x$, we still don’t know which $\omega$ was drawn.

In bits, we have $-\lg p_X(x)$, which is the number of halvings of the possibility space $\Omega$ due to observing $x$. Bits and probabilities can be viewed as different units for the same quantity. $-\lg p_X(x)$ is called the self-information of $x$, and in the Bayesian setting, the surprise due to observing $x$, implying that a higher number of bits makes $x$ more surprising, which makes sense because $x$ caused you to rule out much more of your possibility space.

The connection between $p_X$, information gain $-\lg p_X(x)$, and a physical agent, is that for an agent to have a possibility space, it must have the physical representational capacity. If we presume that a system bounded in a finite region of space contains finite information, i.e. can only occupy finitely many distinguishable states, then our agent must have a finite possibility space $\Omega$ in its model of the environment. Gaining information $-\lg p_X(x)$ requires that the agent physically update its internal possibility space, reducing it by the amount $p_X(x)$. That is to say, information gain quantifies a physical update to an agent. In this sense, subjective information quantifies a change to an agent due to its model of the environment and observations, whereas objective information quantifies a change in the environment.

Note that $p_X$ may be the marginal distribution of $p_{X,H}$, in which case $p_X$ is a subjective data distribution. It is not strictly necessary to actually define hypotheses and priors. $p_X$ can be regarded as a prior, as the end result is the same: the agent has some possibility space, reflecting what the agent is capable of believing, and the proportions of each $x\in\mc{X}$ in that possibility space correspond to how confident the agent is in any given outcome relative to other outcomes.

If $\Omega$ is infinite (countable or uncountable), then we cannot just divide by the size of $\Omega$ to compute probabilities. In this case, we need to provide a measure that tells us how much of the possibility space $\Omega$ any subset is worth, i.e. $P(A)$ for $A \subseteq \Omega$ measures the fraction of $\Omega$ that $A$ is worth even when $\Omega$ and $A$ are infinite. $P$ is called a probability measure, but don’t worry about that. The point is that even in the case of infinite possibilities, we can still think of information gain in terms of narrowing down a possibility space.

Bayesian surprise

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kullback%E2%80%93Leibler_divergence#Mutual_information

Let $\mc{X}$ be data space, $\mc{H}$ be hypothesis space, and $X,H$ be data and hypothesis random variables.

$$

\begin{aligned}

I[X,H] &= \E_X[\kl{p_{H\mid X}}{p_H}] \\

& = \E_{x\sim X}[H(p_{H\mid X=x}, p_H) - H(p_{H\mid X=x})] \\

& = \E_{x\sim X}[\E_{h \sim p_{H\mid X=x}}[-\lg p_H(h)] - \E_{h \sim p_{H\mid X=x}}[-\lg p_{H\mid X}(h \mid x)]] \\

& = \E_{x,h \sim p_{X,H}}\left[\lg \left( \frac{p_{H\mid X}(h\mid x)}{p_H(h)}\right)\right] \\

& = \sum_{x,h \in \mc{X} \times \mc{H}}p_{X,H}(x,h)\lg \left( \frac{p_{H\mid X}(h\mid x)}{p_H(h)}\right) \\

& = \sum_{x,h \in \mc{X} \times \mc{H}}p_{X,H}(x,h)\lg \left( \frac{p_{X,H}(x,h)}{p_X(x)p_H(h)}\right)\,.

\end{aligned}

$$

$I[X,H]$ is called Bayesian surprise, which is the expected (over data) KL divergence from your prior to posterior (after observing data), which is itself the expected difference in uncertainty (measured in bits, the number of halvings of the full possibility space).

Pointwise Bayesian information gain (information gained about hypothesis $h$ from data $x$) is $\lg (1/p_H(h)) - \lg (1/p_{H \mid X}(h \mid x)) = \lg (1/p_X(x)) - \lg (1/p_{X \mid H}(x\mid h))$, which is the change in amount of hypothesis weight (posterior mass) that shifted onto $h$.

$\lg (1/p_{X \mid H}(x \mid h))$ is the surprise (also self-information) of observing $x$ under $h$. The higher this quantity, the more the possibility space of $h$ was narrowed down by $x$.

Variational Bayes

Variational approximation to calculating the Bayesian posterior:

sources:

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Free_energy_principle#Action_and_perception

- A Step-by-Step Tutorial on Active Inference and its Application to Empirical Data

- What does the free energy principle tell us about the brain?

Also see Variational Inference.

Suppose $x\in\mc{X}$ is observed and the posterior $p_{H \mid X=x}$ is intractable to compute. We can instead approximate it by minimizing

$$

q_x^* = \argmin{q \in \mc{Q}} \kl{q}{p_{H \mid X=x}}

$$

where $\mc{Q}$ is some set of probability mass functions $q : \mc{H} \to [0, 1]$, chosen for convenience.

Assuming we cannot perform this minimization directly, we can make use of the identity

$$

\kl{q}{p_{H \mid X=x}} = \mc{F}[q] - \lg (1/p_X(x))

$$

where

$$

\begin{aligned}

\mc{F}[q] &= \kl{q}{p_{H,X=x}} \\

&= \E_{h \sim q} \lg\left(\frac{q(h)}{p_{H,X}(h,x)}\right) \\

&= \sum_{h\in\mc{H}} q(h) \lg\left(\frac{q(h)}{p_{H,X}(h,x)}\right)

\end{aligned}

$$

is the free energy. $\lg (1/p_X(x))$ is the expected surprise of $x$ across all hidden states (weighted by the prior $p_H$).

Free energy also equals

$$

\begin{aligned}

\mc{F}[q] &= H(q, p_{H, X=x}) - H(q) \\

&= \E_{h \sim q}\left[\lg\left(\frac{1}{p_{H, X}(h,x)}\right) - \lg\left(\frac{1}{q(h)}\right) \right] \\

&= \sum_{h \in \mc{H}} q(h) \lg\left(\frac{q(h)}{p_{H,X}(h,x)}\right)\,,

\end{aligned}

$$

where $H(q)$ is the entropy of $q$, and $H(q, p_{H, X=x})$ is the total energy, which is equal to the cross-product of $p_{H, X=x}$ under $q$.

Note that $p_{H, X=x}(h) = p_{H,X}(h,x)$ is not the same as the conditional distribution $p_{H \mid X=x}(h) = p_{H,X}(h,x) / p_X(x)$, and is not a valid probability distribution because its unnormalized.

We also have free energy as complexity minus accuracy,

$$

\begin{aligned}

\mc{F}[q] &= \kl{q}{p_H} - \E_{h\sim q}\left[\lg p_{X \mid H}(x \mid h)\right] \\

&= \E_{h \sim q}\left[\lg\left(\frac{q(h)}{p_H(h)}\right)-\lg p_{X \mid H}(x \mid h)\right] \\

&= \E_{h \sim q}\left[\lg\left(\frac{q(h)}{p_{H,X}(h,x)}\right)\right]\,.

\end{aligned}

$$

This form of free energy can be used in practice. Given any particular $q$ (e.g. as a neural network), the complexity $\kl{q}{p_H}$ and the accuracy $\E_{h\sim q}\left[\lg p_{X \mid H}(x \mid h)\right]$ can be approximated using Monte-Carlo sampling from $q$. This is assuming we have access to a prior $p_H$ over hidden states and predictive (or generative) distribution $p_{X\mid H}$. If $p_{H\mid X}$ is intractable, then a suitable $q^*$ that approximately and sufficiently minimizes $\mc{F}[q]$ becomes our approximation of that posterior.

Note that there is a $q^*$ for every partial observation $x_{1:t}$, i.e. we need to perform another minimization to arrive at $q_{x_{1:t}}^*$ for every $t$.

Bayesian inference over time

I am basing this on Solomonoff induction (as formulated by Marcus Hutter in his book).

We now suppose the agent observes an endless stream of data over time. The full possible set of observations are all infinite sequences $\mc{X}^\infty$ where $\mc{X}$ is the set of possible observations at each point in time, e.g. a frame of sensory data such as a video or audio frame. Let $X_{a:b}$ be the random variable denoting a slice of the data stream from time $a$ to time $b$ (inclusive). $X_{1:n}$ is the first $n$ timesteps of data, and $X_{n+1:\infty}$ is everything that is observed after time $n$. I will also use the shorthands $X_{<n} = X_{1:n-1}$ and $X_{>n} = X_{n+1:\infty}$.

Now suppose the agent has a hypothesis space $\mc{M}$, which is a set of probability distributions $\mu\in\mc{M}$. We call each $\mu$ a hypothesis. Let $\pi$ be a probability distribution over $\mc{M}$ (the prior). Then we have a mixture distribution

$$

p(X_{1:n}) = \sum_{\mu\in\mc{M}} \pi(\mu)\cdot\mu(X_{1:n})\,.

$$

If we define the joint distribution

$$

p(X_{1:n},\mu) = \pi(\mu)\cdot\mu(X_{1:n})\,,

$$

then we have the usual Bayesian quantities:

- Data likelihood: $p(X_{1:n} \mid \mu) = \mu(X_{1:n})$.

- Hypothesis prior: $p(\mu) = \pi(\mu)$.

- Hypothesis posterior: $p(\mu \mid X_{1:n}) = \pi(\mu)\cdot\mu(X_{1:n})/p(X_{1:n})$.

We can think of a finite data sequence $x_{1:n} \in \mc{X}^n$ as a partial observation that the agent updates its mixture weights on:

$$

w_\mu(x_{1:n}) = \pi(\mu)\frac{\mu(x_{1:n})}{p(x_{1:n})}

$$

where the hypothesis posterior is

$$

p(\mu \mid x_{1:n}) = w_\mu(x_{1:n})\,.

$$

We also have a new quantity, the data posterior

$$

p(X_{>n} \mid X_{1:n}=x_{1:n}) = \sum_{\mu\in\mc{M}} w_\mu(x_{1:n})\mu(X_{>n} \mid X_{1:n}=x_{1:n})\,,

$$

which has the same form as the prior mixture, except that we reweighted by switching from $\pi(\mu)$ to $w_\mu(x_{1:n})$, and we conditionalized the hypotheses, i.e. switched from $\mu(X_{1:\infty})$ to $\mu(X_{>n} \mid X_{1:n}=x_{1:n})$.

We can incorporate actions into this framework by specifying that all hypotheses in $\mu\in\mc{M}$ must be distributions over a combined observation and action stream. This stream would be a sequence $(x_1, a_1, x_2, a_2, \ldots)$ of alternating observation $x_t \in \mc{X}$ and action $a_t \in \mc{A}$ at every time step. Note that a hypothesis predicts the next observation $\mu(x_t \mid x_{<t}, a_{<t})$, but we don’t ask a hypothesis to predict a next action, i.e. $a_t$ given $x_{<t}, a_{<t}$, since that is the agent’s decision to make.

Hypotheses vs states; policies vs actions

There is a key distinction to make here: a hypothesis $\mu$ is itself a possible universe. $\mu$ is a distribution over all possible infinite data streams $\mc{X}^\infty$. $\mu$ can be arbitrarily complex, and consider all counterfactual latent states in the universe. $\mu$ may encode the dynamics of a time evolving system in its conditional probabilities $\mu(x_n \mid x_{<n})$. In this way $\mu$ is not a hidden state, but an entire possible universe.

This is in contrast to the idea of a hidden state, which is an unknown state of the universe at some point in time. In the hidden state framework, the environment is defined by a known dynamics distribution $p(x_t, s_t \mid s_{t-1})$ or $p(x_t, s_t \mid s_{t-1}, a_{t-1})$ if we include actions. The only thing that is unknown is $s_{1:t}$. In this framework, knowing $s_{t-1}$ does not mean you know $s_t$ with certainty. In the mixture of hypotheses framework, if you know $\mu$, you know it for all time.

tl;dr: A hypothesis $\mu$ is static and true for all time, and a hidden state $s_t$ evolves and is true only at time $t$.

We also need to make this distinction between policies and actions. A policy $\pi$ (not to be confused with hypothesis prior above, but this is the conventional notation) is similar to $\mu$, in that it is a probability distribution over alternating observations and actions. $\pi(a_t \mid x_{<t}, a_{<t})$ specifies the agent’s action preferences given what it has already seen and done. If we combine an environment $\mu$ and a policy $\pi$, we can fully model the agent-environment interaction loop, i.e. the joint distribution over the space of combined sequences: $\mc{X}\times\mc{A}\times\mc{X}\times\mc{A}\times\ldots$.

tl;dr: A policy $\pi$ is static, i.e. a single agent choice that remains for all time, and an action $a_t$ is a choice made specifically at time $t$.

However, it is possible to devise a setup where there is a set of possible policies $\Pi$, and the agent keeps “changing its mind” about which policy $\pi_t \in \Pi$ to use at time $t$. I find this formulation to be a bit redundant, because $\pi_t$ contains information about the agent’s preferences in all possible future situations, but if the agent changes its mind in the next step then that information is essentially overridden. Why not just have the agent choose an action $a_t$? It could make sense to impose a restriction that $\pi_t$ cannot evolve quickly over time, so that the policy represents a high-level choice about what to do in some time window. This is one avenue for formulating hierarchical decision making.

Free energy principle and time

This is where my understanding falls apart.

I’ve reviewed two sources:

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Free_energy_principle#Action_and_perception

- A Step-by-Step Tutorial on Active Inference and its Application to Empirical Data

1. Wikipedia

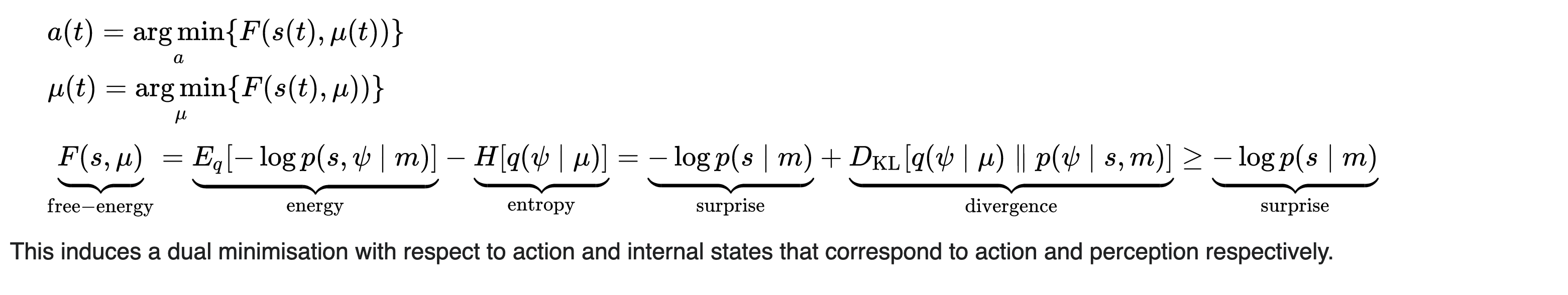

From the first (Wikipedia):

I’m reiterating Wikipedia’s notation here. Overwrite in your brain my usages of $\mu$ and $s$ above.

- $\mu\in R$ is the state of the agent at timestep (not to be confused with hypotheses).

- $a \in A$ is an action taken at every timestep.

- $s \in S$ is an observation at each timestep (not to be confused with environment states).

- $\psi \in \Psi$ is the hidden environment state at every timestep.

Questions:

- What is the Bayesian inference being done here? In my exposition on Bayesian inference over time, the posteriors of interest are explicitly given. I’d like to know what posterior we are interested in approximating with variational free energy here.

- Is this joint minimization being done simultaneously over all timesteps, or is it done in a greedy fashion on every step?

2. Step-by-Step Tutorial

From the second: A Step-by-Step Tutorial on Active Inference and its Application to Empirical Data

The paper opens with an exposition that looks like it matches my own for time-less free energy minimization.

Starting on page 16, we introduce policy $\pi$ (not to be confused with the prior). I’m confused about the relationship between the policy and the time evolution of the environment-agent loop. Does $\pi$ change over time, or is $\pi$ chosen up front and held fixed? Clearly it cannot be held fixed, because then the agent is not utilizing its free energy minimization to alter its behavior.

I’m also confused about the posterior approximation $q$. Now, $q(s \mid \pi)$ depends on the policy. Does this mean we run the free energy minimization for every $\pi$, each producing a different $q$? If that’s so, then why do we not write $q(s_t \mid o_{<t}, \pi)$ to indicate the dependency of $q$ on the observations $o_{<t}$ as well?

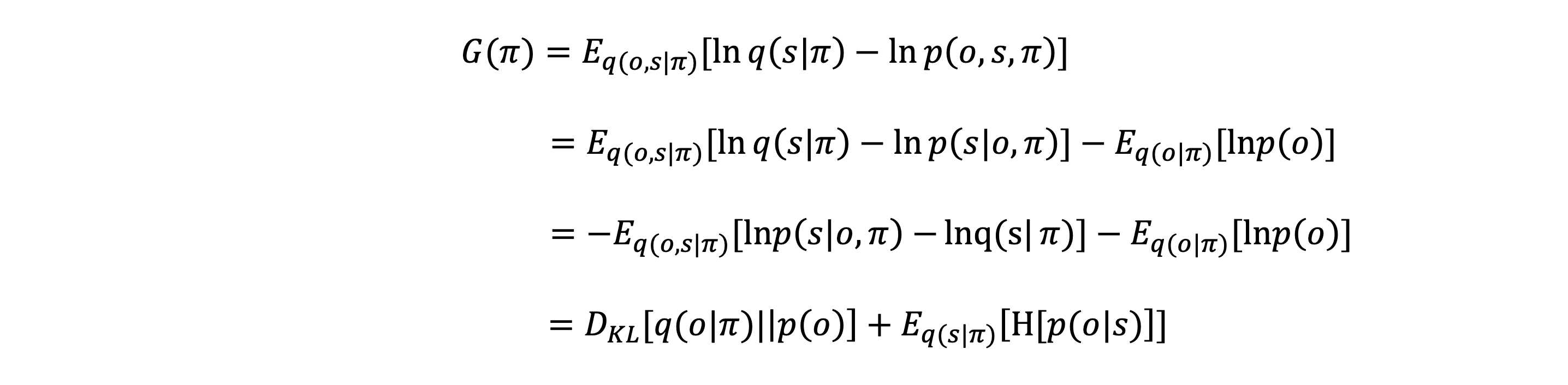

Page 19 adds more confusion to the mix. We are introduced to a score function $G(\pi)$ for choosing policies $\pi$.

First of all, I thought there is a joint distribution $p(o,s,\pi)$, implying that $p(\pi)$ is a prior which reflects the agent’s preferences over policies. So which is it? Does the agent use $G(\pi)$ or $p(\pi)$ to choose its policy? It’s also not clear if $\pi$ is chosen once and held fixed for all time, or if the policy changes over time.

Second, and more perplexing, is that $G(\pi)$ is an expectation over $q(o,s\mid \pi)$, remember that $q$ is an approximate posterior over hidden states $s$. How can $q$ also be a distribution over observations $o$? Trying to make $q$ a joint distribution over $x$ and $h$ in my time-less free energy exposition above doesn’t make sense to me.

My Open Questions

- Is the agent assumed to have a dynamics model of the environment where all that’s unknown to the agent is the environment state? that seems unrealistic. if the agent doesn’t know the “true” dynamics model, by what mechanism would the agent improve its dynamics model? The Bayesian posterior approximation is for estimating the effect of its actions on environment state, but this doesn’t address how the agent learns about the relationship between action and state.

- How are time and actions incorporated? I understand the time-less variational free energy formulation that I explained above. What I don’t understand is what this looks like when applied to an agent-environment interaction loop over time.