[This is an article, which is something I’ve optimized for readability and transmission of ideas, opposed to notes that are the seed of an idea and something I’ve written quickly.]

This a formal description of the Carnot cycle which I hope is a useful reference for anyone who wants to quickly ramp up on thermodynamics. The Carnot cycle is often used as a canonical introduction to classical thermodynamics (specifically the thermodynamics of ideal gasses) since it nicely illustrates the relationship between the entropy, temperature and volume of a gas.

The Carnot cycle is a toy thermodynamic process (read as “thought experiment”) devised by Sadi Carnot in 1824 to derive the first theory of heat efficiency (essentially a proto-thermodynamics). Carnot proves that his hypothetical cycle achieves the theoretically optimal efficiency of any heat engine that converts heat into mechanical work on a piston. Carnot also shows that the optimal efficiency of any transformation is achieved by a reversible process which caries it out, thus establishing the connection between thermodynamics and reversibility (the Carnot cycle is reversible). See The Reversibility Problem for more discussion on that.

Later, Rudolf Clausius reformulated Carnot’s theory and introduced a new concept: entropy. This marks the inception of classical thermodynamics, where entropy is taken as a primitive property of processes involving heat, like energy and mass. Later, Ludwig Boltzmann attempted to derive entropy and classical thermodynamics from Newtonian mechanics, giving rise to statistical thermodynamics.

$$

\newcommand{\0}{\mathrm{false}}

\newcommand{\1}{\mathrm{true}}

\newcommand{\mb}{\mathbb}

\newcommand{\mc}{\mathcal}

\newcommand{\mf}{\mathfrak}

\newcommand{\ms}{\mathscr}

\newcommand{\and}{\wedge}

\newcommand{\or}{\vee}

\newcommand{\es}{\emptyset}

\newcommand{\a}{\alpha}

\newcommand{\t}{\tau}

\newcommand{\T}{\Theta}

\newcommand{\D}{\Delta}

\newcommand{\o}{\omega}

\newcommand{\O}{\Omega}

\newcommand{\x}{\xi}

\newcommand{\z}{\zeta}

\newcommand{\fa}{\forall}

\newcommand{\ex}{\exists}

\newcommand{\X}{\mc{X}}

\newcommand{\Y}{\mc{Y}}

\newcommand{\Z}{\mc{Z}}

\newcommand{\P}{\Psi}

\newcommand{\y}{\psi}

\newcommand{\p}{\phi}

\newcommand{\l}{\lambda}

\newcommand{\L}{\Lambda}

\newcommand{\G}{\Gamma}

\newcommand{\g}{\gamma}

\newcommand{\B}{\mb{B}}

\newcommand{\m}{\times}

\newcommand{\N}{\mb{N}}

\newcommand{\I}{\mb{I}}

\newcommand{\H}{\mc{H}}

\newcommand{\R}{\mb{R}}

\newcommand{\s}{\sigma}

\newcommand{\e}{\varepsilon}

\newcommand{\set}[1]{\left\{#1\right\}}

\newcommand{\par}[1]{\left(#1\right)}

\newcommand{\tup}{\par}

\newcommand{\vtup}[1]{\left\langle#1\right\rangle}

\newcommand{\abs}[1]{\left\lvert#1\right\rvert}

\newcommand{\inv}[1]{{#1}^{-1}}

\newcommand{\ceil}[1]{\left\lceil#1\right\rceil}

\newcommand{\dom}[1]{_{\mid #1}}

\newcommand{\df}{\overset{\mathrm{def}}{=}}

\newcommand{\M}{\mc{M}}

\newcommand{\up}[1]{^{(#1)}}

\newcommand{\Dt}{{\Delta t}}

\newcommand{\tr}{\rightarrowtail}

\newcommand{\qed}{\ \ \blacksquare}

\newcommand{\c}{\overline}

\newcommand{\dg}{\dagger}

\newcommand{\dd}{\mathrm{d}}

\newcommand{\pd}{\partial}

\newcommand{\diff}[2]{\frac{\dd{#2}}{\dd{#1}}}

\newcommand{\Ue}{U_{\text{ext}}}

\newcommand{\Ui}{U_{\text{int}}}

$$

Prerequisites

I will derive everything below from the laws of classical mechanics, plus three additional useful equations characterizing ideal gasses.

For an ideal gas at equilibrium with pressure $P$, volume $V$, temperature $T$, gas constant $R$ (depends on the type of gas), and number of moles $n$ of gas (i.e. number of particles divided by the Avogadro constant), the ideal gas law states that

$$

PV=nRT\,.

$$

All the equilibrium states of the gas are fully described by the triple $(P,V,T)$, with one of the three being redundant due to the ideal gas law. In this post, I will use $(T,V)$ to describe the state of the gas at equilibrium.

For an ideal gas initially at equilibrium with volume and temperature $V_i,T_i$, and later at equilibrium again with final volume and temperature $V_f,T_f$, the change in entropy of this gas is (source 1, source 2, source 3)

$$

\D S = nC_V \ln\par{\frac{T_f}{T_i}} + nR \ln\par{\frac{V_f}{V_i}}\,,

$$

where $C_V$ is the molar heat capacity at a constant volume (another constant that depends on the type of gas) and $R$ is the gas constant. In the context of this post, this is the definition of entropy, which will be taken as a primitive quantity. This definition is agnostic to how we define the absolute entropy of a gas at a particular temperature and volume. Only changes in entropy will be considered in this post.

Note that the gas only needs to be at equilibrium at the start and end of the transformation and need not be in equilibrium during the change. This is because entropy is a state variable, which means that the entropy of a system only depends on its current state (if the entropy is well defined in its current state), and not the path the system took to get to its current state. This allows us to calculate changes in entropy for processes with undefined entropy during intermediate steps. In this post, the entropy of a gas is not defined outside of equilibrium.

The internal energy of an ideal gas is the total kinetic energy (KE) of all the particles of the gas. When in equilibrium, the temperature $T$ of the gas is proportional to the average KE across all the degrees of freedom of the gas (e.g. the $x$, $y$ and $z$ axes for each particle). Then the total KE is proportional to $T$ and $n$ (proportional to the number of particles in the gas). We have the internal energy of the gas,

$$E_\text{int} = nC_VT\,,$$

where again, $n$ is the number of moles of the gas and $C_V$ is the molar heat capacity at a constant volume.

Note that some texts use specific heat capacity at constant volume, $c_v$, which is written as lower-case, instead of the molar specific heat, $C_V$. They’re related by $c_v = nC_V$.

Phases Of The Carnot Cycle

The Carnot cycle consists of four phases (or steps), involving a gas in a container (which I’ll refer to simply as “the gas”) with a movable wall called “the piston”. Those four phases are, #1 Isothermal expansion, #2 Isentropic adiabatic expansion, #3 Isothermal compression and #4 Isentropic adiabatic compression.

During the cycle, the piston pushes against the gas with some force. The magnitude of that force determines whether the container is expanding or compressing (whether the force the piston exerts is less than or greater than the gas’s pressure against the container walls). The piston is what we use to do work, e.g. pushing a mass up against gravity or pushing the wheels of a train against friction. The resistance against the piston determines the force the piston applies against the gas. We can simplify this all as a potential energy field that the piston lies in as a function of the piston’s position.

Illustration of a piston doing mechanical work - in this case rotating a wheel (for example, this could be applied to a locomotive): Illustration of a piston. Source: https://lawofthermodynamicsinfo.com/what-is-carnot-cycle-in-thermodynamics/

At various phases in the cycle, the gas may or may not be in thermal contact with heat reservoirs (each phase defines which heat reservoirs are present). Heat reservoirs are idealized systems with infinitely many degrees of freedom (e.g. particle positions) which maintain their temperature no matter how much heat energy is added or subtracted. For example, a gas with infinitely many particles occupying infinite volume. A heat reservoir that provides heat energy output is called a heat source, and a heat reservoir that absorbs heat energy input is called a heat sink. Heat sources are often called “hot” and heat sinks are often called “cold”.

This animation illustrates the four phases in action. To understand the details of what is happening, please refer to the formal definition of each phase in the following sections. Source: https://www.saburchill.com/physics/chapters/0124b.html

This diagram shows the four phases with variable amounts of mass applied to the piston. In the following sections I go in depth in calculating what those masses should be and how they should change throughout the cycle, since this can be a point of confusion. Source: https://www.grc.nasa.gov/www/k-12/airplane/carnot.html

Also, this video is a good illustration of the carnot cycle in action (with particle level simulation of the gas): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M6XQi8eYYNs

All phases of the Carnot cycle are quasistatic, which means that the process stays close to equilibrium during the changes that take place. What this means for us is that we can assume that the entropy, temperature, volume and pressure of the gas are always well defined through out each phase. The quasistatic assumption is needed to ensure that every phase of the cycle is reversible, which makes the cycle as a whole reversible.

The net result of the Carnot cycle is that energy is extracted from a heat source to move a piston (do useful work), but not entirely so (see discussion on #Efficiency). Some of the energy is dumped into a heat sink as waste. However, that waste heat is recoverable. The Carnot cycle is reversible. When run in reverse, heat energy is extracted from a cold reservoir, and combined with work added by the piston, to produce heat energy dumped into the hot reservoir. The reverse Carnot cycle is a heat pump that moves heat from cold to hot, i.e. a refrigerator where the cold reservoir is the inside that we are keeping cold. If during the Carnot cycle and waste heat is not dumped into the heat sink but instead lost to the ambient environment, that is energy which cannot be recovered in the reverse cycle, making the forward cycle irreversible.

1. Isothermal expansion

Reference: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Isothermal_process

An animation of isothermal compression and its reversal, isothermal expansion. The temperature and mass of the gas (number of particles) is held fixed. Here mass is placed on top of the piston to provide a force. That force must be continuously adjusted over time for the piston to move. Source: https://www.grc.nasa.gov/www/k-12/airplane/boyle.html

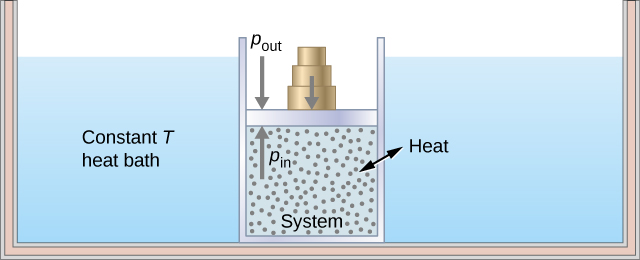

This shows the heat reservoir for the isothermal process. Source: https://opentextbc.ca/universityphysicsv2openstax/chapter/thermodynamic-processes/

Let the gas start this phase in equilibrium at temp $T_i$ and volume $V_i$ (confined to a container).

As the name of this phase suggests, the container will expand to a new volume $V_f$, with the constraint that the temperature of the gas remains constant, so that $T_i=T_f=T_H$ ($T_H$ is the “hot” temperature). Hence the adjective “iso”-“thermal”. This is achieved by keeping the container (and thus the gas) in thermal contact with a heat reservoir which maintains a temperature $T_H$ during the expansion. This reservoir is a heat source since in this phase we will exact heat energy from it to do work.

Using the change in entropy definition above, we have the change in entropy of the gas during phase 1:

$$\begin{aligned}\D S\up{1}&= nC_V \ln\par{\frac{T_H}{T_H}} + nR \ln\par{\frac{V_f}{V_i}} \\ &= nR \ln\par{\frac{V_f}{V_i}}\,.\end{aligned}$$

Let’s suppose the gas container has an extruded shape (has a fixed cross-sectional profile), where one end of the extruded profile is capped off with a movable wall (i.e. piston) with area $A$. If $x$ is the length of the container (which is also the position of the piston), then the volume of the container is $V(x) = Ax$. Then the initial and final volumes of the gas are $V_i=Ax_i$ and $V_f=Ax_f$ respectively, so that we have $\D S\up{1} = nR \ln\par{\frac{x_f}{x_i}}$, which depends only on the piston’s position.

Let $U(x)$ be the potential energy of the piston at position $x$ so that the piston pushes on the gas with force $F = -U'(x) = -\frac{\dd}{\dd{x}}U(x)$, i.e. this force is the negative spatial derivative of the scalar potential field $U$. For example, if the piston is pushing a mass $m$ against gravity, then $U(x)=mgx$ with gravitational constant $g$, and so $F = -U'(x) = -mg$.

The net work done by the gas on the piston in phase 1 is $W\up{1} = U(x_f)-U(x_i)$, since the forces involved here are conservative by necessity, as they are derived from the derivative of a potential field. In this case we say that the work done is path independent.

The work done by the gas on the piston equals heat energy $Q_H$ extracted from the heat source, so we have $Q_H = W\up{1}$. Since the temperature of the gas remains constant, the internal energy of the gas is also constant. Thus any heat energy converted into work on the piston must come from the heat source. So in phase 1, the source provides heat energy $Q_H$ as input to the Carnot cycle.

This phase has no determined end. The user is free to choose $x_f > x_i$, which is the point at which the user switches the process to phase 2. The choice of $x_f$ determines how much work will be done on the piston during the cycle, but the efficiency of the cycle is independent of $x_f$. See #Choosing the end of phase 1 for details.

Potential calculation

The potential function $U(x)$ is actually fully determined by the given contraints, i.e. we must choose a particular $U(x)$ if we want phase 1 to be quasistatic (approx. at equilibrium at all times) and reversible. Let’s derive $U(x)$.

For this process to be quasistatic, the force $F(x)=-U'(x)$ that the piston exerts on the gas needs to equal the force the gas exerts on the container at all times, i.e. $F(x)=-AP(x)$, and so $U'(x)=AP(x)$ for all $x$, where $A$ is area and the pressure $P(x)$ is force per area.

Technically, if the piston’s force and gas pressure are exactly balanced then the piston won’t move. Assuming the gas was already at equilibrium, then it continues to be at equilibrium since nothing happens. If we suppose that the piston pushes against the gas with slightly less force than the gas exerts on the piston, then the piston is pushed out (the container expands). So we have $F(x)+\e=-AP(x)$ where $\e > 0$ is small. If this difference in forces $\e$ is small enough, we can fudge things and suppose the gas remains close to equilibrium during the change (the meaning of quasistatic), and that $\e$ is negligable and doesn’t need to be modeled, i.e. let $\e=0$ (we could call $\e$ infinitessimal). If you don’t find this explanation satisfying, perhaps an alternative conceptualization in #A note about quasistatic processes would be more convincing.

Rearranging the ideal gas law, we have $P(x) = nR\frac{T(x)}{V(x)}$, where $T(x)=T_H$ and $V(x)=Ax$. Plugging this into $U'(x)=AP(x)$, we get $U'(x)=AnR\frac{T_H}{Ax}=nR\frac{T_H}{x}$. Integrating, we get $$U(x)=\int_{x_i}^{x} nR\frac{T_H}{x} \dd{x}=nRT_H\ln\par{\frac{x}{x_i}}\,.$$

Note that $U(0)=0$, i.e. we are setting the zero potential at the initial position $x_i$ (potential functions are invariant up to an additive constant, i.e. absolute potential energies are arbitrary, the physically meaningful quantities are changes in potential). Thus, the cumulative work done on the piston by the gas at any point in the phase 1 process is $W(x)=U(x)-U(x_i)=U(x)=nRT_H\ln\par{\frac{x_f}{x_i}}$.

But then, how are we free to choose what the piston acts on? E.g. earlier I gave the examples of the piston pushing a mass against gravity, or pushing the wheels of a train. These applications also determine $U(x)$, and so it would seem our problem is over-constrained. It must be the case that some other parameter in the potential function is itself a function of $x$.

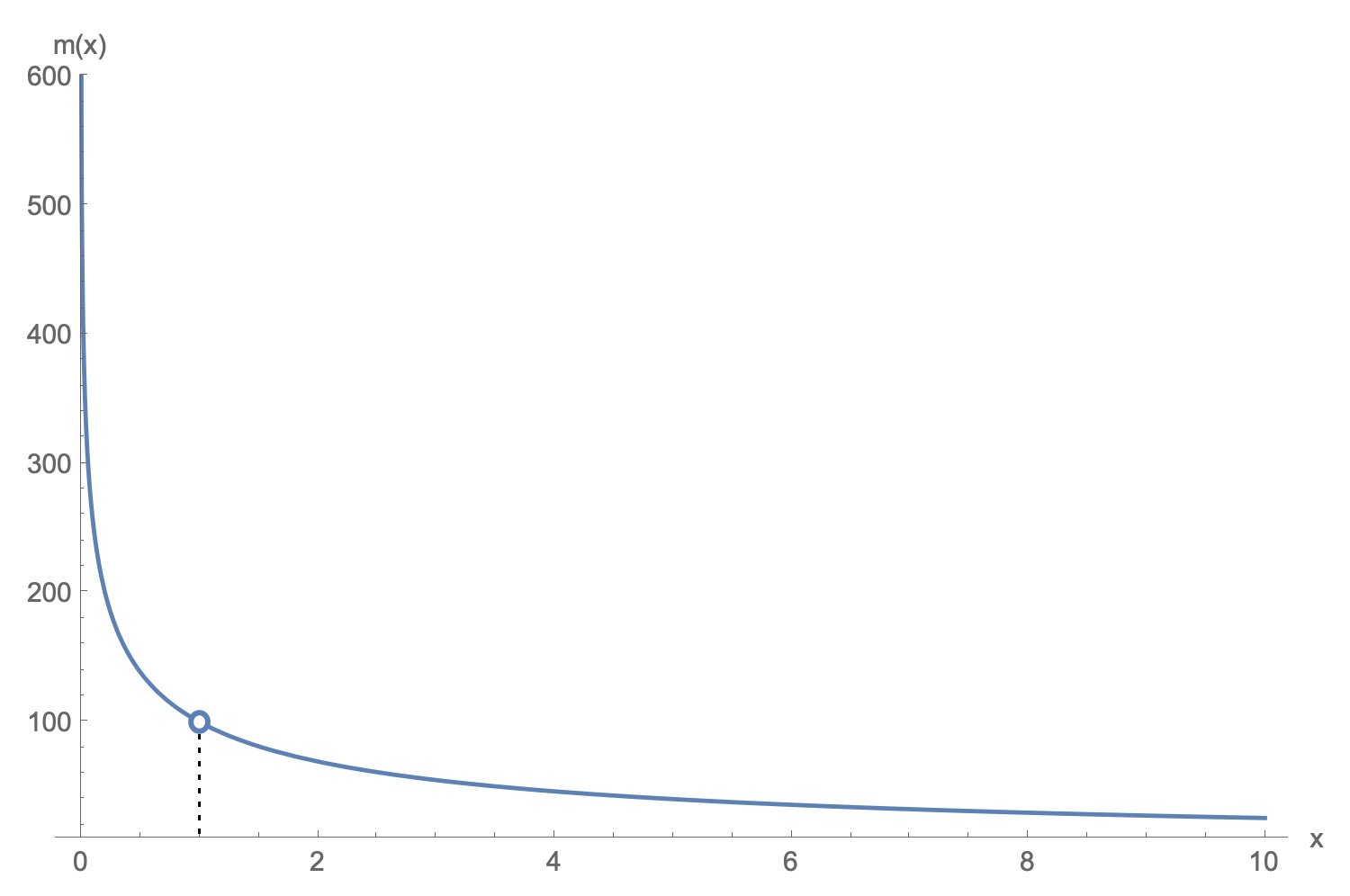

In the case where the piston is pushing a mass against gravity, the gravitational potential is $U(x)=mg(x-x_i)$ where $U(0)=0$. Assuming we are close to the surface of the earth so that $g$ is constant, then our only choice is to make $m$ variable, i.e. $m$ becomes $m(x)$, a function of $x$. We find $m(x)$ by setting the gravitational potential equal to the potential function that makes phase 1 quasistatic:

$$\begin{aligned}m(x)\cdot g\cdot(x-x_i)&=nRT_H\ln\par{\frac{x}{x_i}} \\ m(x)&=\frac{nRT_H}{g}\ln\left[\par{\frac{x}{x_i}}^{1/(x-x_i)}\right]\,.\end{aligned}$$

Note that there is a hole in this function at $x=x_i$, but we can fill it in by taking the limit:

$$

\lim_{x\to x_i}\frac{nRT_H}{g}\ln\left[\par{\frac{x}{x_i}}^{1/(x-x_i)}\right] = \frac{nRT_H}{gx_i}

$$

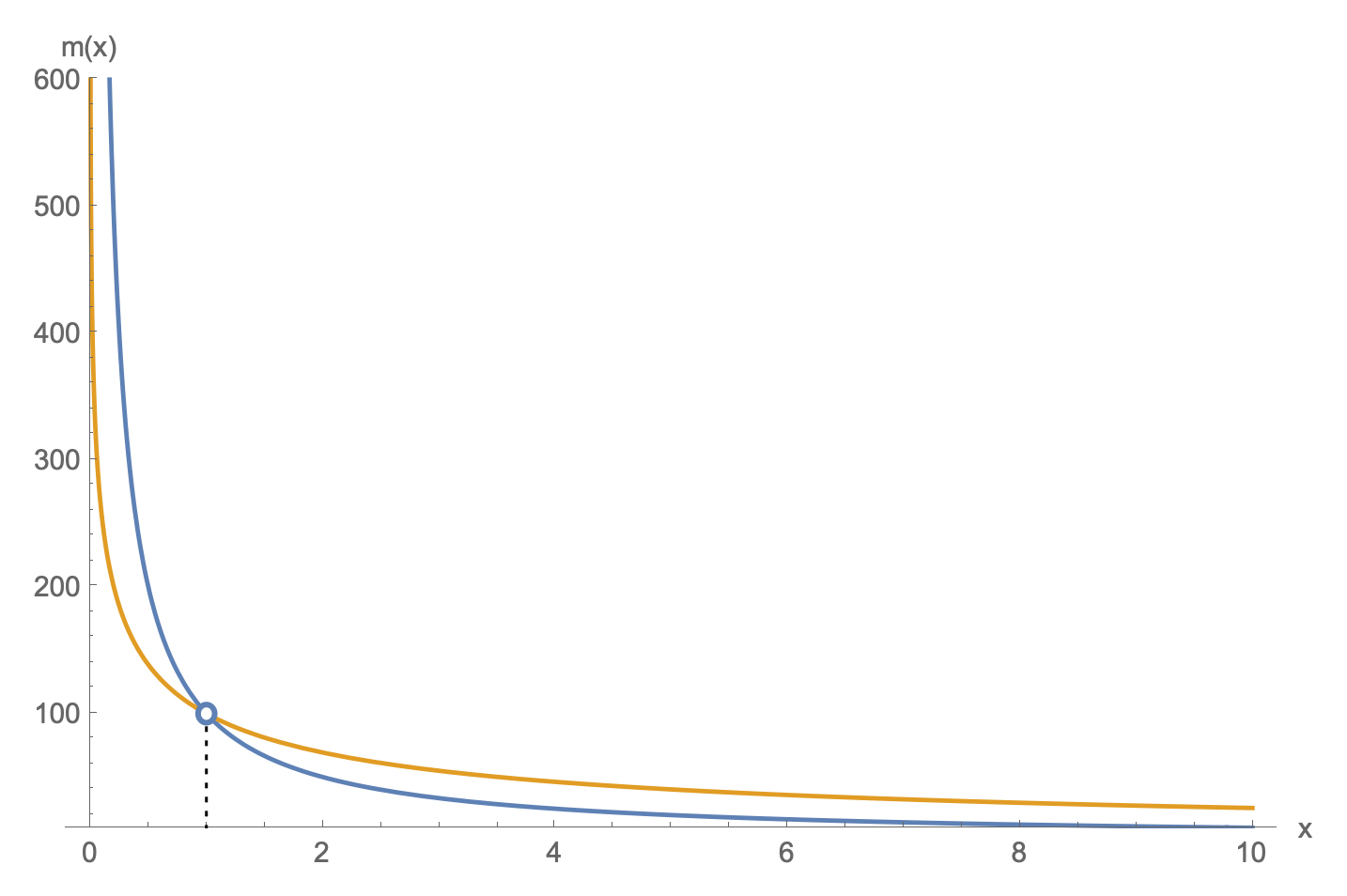

An example plot of $m(x)$ with the hole at $x_i$ shown.

A note about quasistatic processes

Another way to think about this phase 1 quasistatic process is that we are finding a potential field $U(x)$ s.t. at every $x$ the forces of the piston and gas are exactly balanced, which implies the piston and gas will be static at equilibrium for all $x$ (temperature and position will remain constant without external intervention).

The idea of a quasistatic transformation is that the otherwise static system is repeatedly nudged slightly out of equilibrium from the outside over and over again, where the system is allowed to return to equilibrium in between each nudge. This nudging from the outside is how changes to $x$ and $T$ are driven and controlled. For example, if the piston’s force on the gas is due to mass resting on top of the piston and the piston is at position $x$, if the operator changes that mass from $m(x)$ to $m(x+\e)$ for some small $\e > 0$, then the gas will push the piston out until the piston position becomes $x+\e$ where the forces are again balanced. Technically, since the gas momentarily left equilibrium during this change, we should expect some inefficiency in the form of irreversible gain of entropy. The fudge is now that we neglect that inefficiency and assume an ideal reversible transformation.

2. Isentropic (adiabatic) expansion

Reference: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Isentropic_process

Let the gas start this phase at temp $T_i$ and volume $V_i=Ax_i$, with piston area $A$ and container length $x_i$. I hope it is not confusing if I use “initial” and “final” variables to refer to the start and end of each phase separately, so that phase 2 initial temperature equals phase 1 final temperature and phase 2 initial volume equals phase 1 final volume. Thus $T_i = T_H$. I’ll use superscripts to distinguish variables from different phases when they appear together, so we have $x_i\up{2} = x_f\up{1}$, meaning that the initial piston position of phase 2 (this phase) equals the final piston position of phase 1 (the last phase).

This phase is defined by the constraint that the gas remains at constant entropy (hence “iso”-“entropic”). Then let

$$\D S\up{2}=0\,,$$

so that $0 = nC_V \ln\par{\frac{T_f}{T_i}} + nR \ln\par{\frac{x_f}{x_i}}$, where we plugged in $V_i=Ax_i$ and $V_f=Ax_f$. Note that the gas is not in thermal contact with any heat reservoir in this phase. Then any energy transferred to the piston (as potential energy) must come from the internal energy of the gas, lowering the temperature of the gas. (In general, compression or expansion of a thermally isolated gas need not be isentropic. The piston must move in a specific way for the gas’s entropy to remain unchanged.)

If we assume the user stops phase 2 at $x_f > x_i$, then we can solve for the final temperature $T_f$ using the change in entropy formula:

$$\begin{aligned}\ln T_f&=\ln T_i + \frac{R}{C_V} \ln\par{\frac{x_i}{x_f}}\\

T_f&=T_i\par{\frac{x_i}{x_f}}^{R/C_V}\,.\end{aligned}$$

Note that $T_f < T_i$ when $x_f > x_i$, implying that energy is transferred from the gas to the piston as potential energy.

The work done by the gas on piston in phase 2 is $W\up{2} = U(x_f)-U(x_i)$. As was said before, the energy for that work comes entirely from the gas itself as internal energy (i.e. KE of the gas particles). Then we have $\D E_\text{int}\up{2} = -W\up{2}$, i.e. change in internal (heat) energy of the gas equals negative amount of energy used to do work (energy outflow). Using the internal energy formula of an ideal gas, we have

$$\D E_\text{int}\up{2} = nC_V\D T = nC_V(T_f-T_i)\,.$$

Then the work done on the piston by the gas during phase 2 is $W\up{2}=-\D E_\text{int}\up{2}=nC_V(T_i-T_f)$

Let $T_f = T_C$, which is the temperature of a cold heat reservoir (heat sink) that will be used in phase 3. Combined with $T_i = T_H$, we have

$$W\up{2}=nC_V(T_H-T_C)\,.$$

Potential calculation

Again we are constrained to a particular $U(x)$ by requiring that phase 2 be quasistatic. As in phase 1, we have $U'(x)=AP(x)=AnR\frac{T(x)}{V(x)}=nR\frac{T(x)}{x}$ where $V(x)=Ax$. Now temperature also is variable. Specifically, $T(x)=T_i\par{\frac{x_i}{x}}^{R/C_V}$, which we derived earlier (replacing $x_f$ with $x$ and $T_f$ with $T(x)$).

Plugging in to $U'(x)$, we get $U'(x) = nR\frac{1}{x}T_i\par{\frac{x_i}{x}}^{R/C_V}$. Integrating, we get

$$\begin{aligned}

U(x)&=\int_{x_i}^x U'(\chi)\dd{\chi}\\&=nC_V T_i\par{1-\par{\frac{x}{x_i}}^{-R/{C_V}}}\\&=nC_V\Big(T_i-T(x)\Big)\,.

\end{aligned}$$

As a sanity check, we get the same result if we instead perform the following derivation: $U(x)=U(x)-U(x_i)=W(x)=-\D E_\text{int}(x) = -nC_V\Big(T(x)-T_i\Big)$, where $U(x_i)=0$, and $W(x)$ and $\D E_\text{int}(x)$ are the cumulative work done and change in gas internal energy respectively.

Again, if we are using the gravitational potential $U(x)=m\cdot g\cdot (x-x_i)$ so that $U(0)=0$, then $m$ must become $m(x)$, a function of $x$. Then

$$\begin{aligned}m(x)\cdot g\cdot(x-x_i)&=nC_V\Big(T_i-T(x)\Big) \\ m(x)&=\frac{nC_V}{g}\par{\frac{T_i-T(x)}{x-x_i}} \\ m(x)&=\frac{nC_V}{g}T_i\par{\frac{1-\par{\frac{x_i}{x}}^{R/C_V}}{x-x_i}}\,.\end{aligned}$$

In phase 2, $T(x) \leq T_i$ and $x \geq x_i$, so this quantity is positive.

This function also has a hole at $x=x_i$. Taking the limit, we have

$$

\lim_{x\to x_i}\frac{nC_VT_i}{g}\par{\frac{1-\par{\frac{x_i}{x}}^{R/C_V}}{x-x_i}} = \frac{nRT_i}{gx_i}\,,

$$

which is the same limit at $x_i$ as the mass function from phase 1.

Plot of $m(x)$ in blue with the hole at $x_i$ shown. The orange plot is the mass function from phase 1 for comparison. Both share the same hole.

3. Isothermal compression

The purpose of the remaining two phases is to return the gas to its initial state (from phase 1), completing the cycle. This is achieved by running phase 1 in reverse (phase 3) and then phase 2 in reverse (phase 4). Note that this is not equivalent to reversing the joint 1+2 process (that would requiring reversing phase 2 and then phase 1), and the result is a net transfer of energy from the heat source to the heat sink and piston by the end of the cycle. So while the gas itself is reset (making the four phases a cycle), the environment has a net change. In this way, the useful work we get out of the first two phases is not entirely undone by the next two phases (otherwise the Carnot cycle would be useless).

As promised, phase 3 is phase 1 in reverse, with $T_i=T_f=T_C$ where $T_C<T_H$ is the “cold” temperature, i.e. temperature of a heat reservoir that is colder than the hot reservoir. The initial piston position in this phase is the final piston position from the last phase.

This phase is isothermal, so we have

$$\D S\up{3} = nR \ln\par{\frac{x_f}{x_i}}\,.$$

Unlike in phase 1, in phase 3 we have $x_f < x_i$ which means $\D S\up{3} < 0$.

Unlike phases 1 and 2, the final positions of phases 3 and 4 are determined by the requirement that the net change in entropy of the gas at the end of the cycle be zero (this is what it means for the cycle to be reversible), i.e. $\D S=\D S\up{1}+\D S\up{2}+\D S\up{3}+\D S\up{4}=0$.

Since $\D S\up{2}=\D S\up{4} = 0$ (both phases are isentropic), we must have

$$\D S\up{3} = -\D S\up{1}\,.$$

Let $x_i\up{1},\ x_f\up{1}$ be the initial and final piston positions in phase 1, and $x_i\up{3},\ x_f\up{3}$ be the initial and final piston positions in phase 3. Using $\D S\up{1} = nR \ln\par{\frac{x_f\up{1}}{x_i\up{1}}}$ and $\D S\up{3} = nR \ln\par{\frac{x_f\up{3}}{x_i\up{3}}}$, we have

$$\begin{aligned}

nR \ln\par{\frac{x_f\up{1}}{x_i\up{1}}} &= -nR \ln\par{\frac{x_f\up{3}}{x_i\up{3}}} \\

\frac{x_f\up{3}}{x_i\up{3}} &= \frac{x_i\up{1}}{x_f\up{1}} \\

x_f\up{3}&=x_i\up{3}\frac{x_i\up{1}}{x_f\up{1}}\,.

\end{aligned}$$

Using the potential function $U(x)=nRT_H\ln\par{\frac{x}{x_i}}$ that we derived in phase 1, we calculate the work done on the piston by the gas: $$W\up{3}=U(x_f\up{3})-U(x_i\up{3})=nRT_C\ln\par{\frac{x_f\up{3}}{x_i\up{3}}}\,.$$

Phase 3 is doing compression, i.e. $x_f < x_i$. Then $W\up{3} < 0$, indicating that the piston is doing positive work on the gas, i.e. transfer of piston potential energy back into the gas as heat energy. That would heat up the gas, but the gas is in thermal contact with the cold reservoir, so the heat energy is transferred there (making it a heat sink), and the gas’s temperature remains fixed at $T_C$. As in phase 1, the work done on the piston is fully accounted for by the heat energy exchanged by the heat reservoir, i.e. $Q_C = W\up{3}$. However, this time, since the piston is doing work on the gas, $W\up{3}$ is negative indicating that $Q_C$ negative, meaning we are depositing heat energy of magnitude $\abs{Q_C}$ into the heat sink. Thus in phase 3, the Carnot cycle produces heat energy $\abs{Q_C}$ as output.

4. Isentropic (adiabatic) compression

This is phase 2 in reverse.

$\D S\up{4}=0$.

Work done on the piston by the gas is $W\up{4}=-nC_V\D T = nC_V(T_i-T_f)=nC_V(T_C-T_H)=-W\up{2}$ where $T_C=T_i$ and $T_H=T_f$.

We require that $x_f\up{4} = x_i\up{1}$ to complete the cycle.

Entropy Of The Environment

The total entropy across the gas and the heat reservoirs remains fixed.

Because the heat reservoirs are infinite in size and are held at constant temperature, their change in entropy is not well defined. However, we can approach this ideal by considering finite heat reservoirs, i.e. other gasses in containers which are much larger than the gas being manipulated. If we suppose the heat reservoir containers remains fixed in volume, then their temperature changes slightly when heat energy is added or removed. Then the isothermal steps are not perfectly held at fixed temperatures.

Let’s see how the motion of the piston would differ if we enforced that the total change in entropy across the gas and the reservoir is fixed at 0. Then we have something similar to the isentropic phases 2 and 4, except we are considering the heat reservoir and the gas together. Let $n$ be the molar mass of the gas, and $N$ be the molar mass of the heat reservoir (a much larger gas). We assume that the gas and reservoir are always at the same temperature. The reservoir occupies some constant large fixed volume, whereas the gas changes in volume depending on the positions $x_i$ and $x_f$ of the piston. Then given no change in entropy, we have

$$

0 = (n+N)C_V \ln\par{\frac{T_f}{T_i}} + nR \ln\par{\frac{x_f}{x_i}}\,.

$$

Then

$$\begin{aligned}\ln T_f&=\ln T_i + \frac{n}{n+N}\frac{R}{C_V} \ln\par{\frac{x_i}{x_f}}\\

T_f&=T_i\par{\frac{x_i}{x_f}}^{\g}\,,\end{aligned}$$

where $$\g = \frac{n}{n+N}\frac{R}{C_V}\,.$$

The work done on the gas by the piston equals the negative change in internal energy of the combined gas and reservoir:

$$\begin{aligned}

W &= -\D E_\text{int} = (n+N)C_V(T_i-T_f) \\

&= (n+N)C_VT_i\par{1-\par{\frac{x_i}{x_f}}^{\g}} \,.

\end{aligned}$$

Taking the size of the reservoir to infinity, $N\to\infty$, we approach an isothermal process, since $\g \to 0$ and so $T_f \to T_i$. Then taking the limit of work should give us the formula for work from phase 1:

$$

\lim_{N\to\infty} (n+N)C_VT_i\par{1-\par{\frac{x_i}{x_f}}^{\frac{n}{n+N}\frac{R}{C_V}}} = nRT_i \ln \left(\frac{x_f}{x_i}\right)

$$

which indeed agrees with phase 1 work $W\up{1}$, where $T_i = T_H$.

Approaching isothermality as a limit allows us to consider the entropy of the reservoir for large but still finite $N$. For the gas,

$$\begin{aligned}

\D S_\text{gas} &= \lim_{N\to\infty} nC_V \ln\par{\frac{T_f}{T_i}} + nR \ln\par{\frac{x_f}{x_i}} \\

&= \lim_{N\to\infty} nC_V \ln\par{\frac{T_i\par{\frac{x_i}{x_f}}^{\g}}{T_i}} + nR \ln\par{\frac{x_f}{x_i}} \\

&= \lim_{N\to\infty} -\frac{n^2}{n+N}R \ln\par{\frac{x_f}{x_i}} + nR \ln\par{\frac{x_f}{x_i}} \\

&= \lim_{N\to\infty} \frac{n(n+N)-n^2}{n+N}R \ln\par{\frac{x_f}{x_i}} \\

&= \lim_{N\to\infty} \frac{nN}{n+N}R \ln\par{\frac{x_f}{x_i}} \\

&= nR \ln\par{\frac{x_f}{x_i}}\,,

\end{aligned}$$

which agrees with the phase 1 change in entropy $\D S\up{1}$.

We setup the problem with the constraint that total entropy is conserved, and so it must be the case that $\D S_\text{reservoir} = -\D S_\text{gas}$. But as a sanity check, let’s compute $\D S_\text{reservoir}$ as $N\to\infty$,

$$\begin{aligned}

\D S_\text{reservoir} &= \lim_{N\to\infty} NC_V \ln\par{\frac{T_f}{T_i}} \\

&= \lim_{N\to\infty} NC_V \ln\par{\frac{T_i\par{\frac{x_i}{x_f}}^{\g}}{T_i}} \\

&= \lim_{N\to\infty} -\frac{nN}{n+N}R\ln\par{\frac{x_f}{x_i}} \\

&= -nR\ln\par{\frac{x_f}{x_i}}\,,

\end{aligned}$$

which equals $-\D S\up{1}$.

This is why the isothermal phases are reversible even though the entropy of the gas changes. An increase in entropy alone does not make a process irreversible. So long as some other part of the universe decreases in entropy by the same amount, and that part can still interact with the process of interest, then the process of interest may still be reversible. Canonical irreversible processes like free expansion, heat exchange, and gas mixing, all involve an increase in entropy without any corresponding decrease in entropy somewhere else. We encounter irreversibility because unlike energy, entropy is not a conserved quantity, but rather a monotonic quantity. That is to say, the total entropy of an isolated system cannot decrease, but it can increase.

Efficiency

The efficiency of a thermodynamic process is defined as

$$

\eta = \frac{W_\text{out}}{E_\text{in}}\,,

$$

where $W_\text{out} \geq 0$ is the useful work that we get out of the process (i.e. energy put towards making a desired change in the world), and $E_\text{in} \geq 0$ is the energy removed from some source. In practice, the denominator is energy released from some energy storage, e.g. chemical potential stored in oil, or nuclear potential stored in uranium. So the efficiency of a power plant is the amount of work extracted (to rotate a giant magnet producing an electric current) per energy released from the fuel.

If we’ve are accounted for all energy moving into and out of the process, then by necessity $E_\text{in} = W_\text{out} + E_\text{unused}$, with $E_\text{unused} \geq 0$ implying $0\leq \eta \leq 1$. The difference $E_\text{unused} = E_\text{in} - W_\text{out}$ is the remaining energy extracted from the source which was not put towards useful work. Usually, this unused energy is released into the environment as ambient heat - an irreversible operation (an instance of heat transfer through a finite temperature difference). In the reversible Carnot cycle, the heat sink (cold reservoir) absorbs all the unused energy as heat. In the reverse Carnot cycle, that energy is extracted from the sink (which becomes the source), and the piston provides additional input energy (equal to $W_\text{out}$).

Let’s calculate the efficiency of the Carnot cycle. $W_\text{out}$ is the net work done by the four phases, and $E_\text{in}$ is the net heat energy extracted from the heat source across the four cycles.

Since the only contact with the heat source is in phase 1, where $Q_H$ heat energy was extracted, then $E_\text{in} = Q_H = W\up{1} = nRT_H\ln\par{\frac{x_f\up{1}}{x_i\up{1}}} = T_H\D S\up{1}$. Recall from phase 1 that $\D S\up{1}=nR \ln\par{\frac{x_f\up{1}}{x_i\up{1}}}$, which is the amount of entropy gained by the gas during isothermal expansion.

Likewise, the only contact with the heat sink is in phase 3, where $\abs{Q_C}$ heat energy was added to the sink. Then $E_\text{unused} = \abs{Q_C} = \abs{W\up{3}}=\abs{T_C\D S\up{3}}=T_C\D S\up{1}$ since $\D S\up{1} = -\D S\up{3}$.

$W_\text{out}$ is the total work done across the four phases, i.e.

$$\begin{aligned}

W_\text{out} &= W\up{1}+W\up{2}+W\up{3}+W\up{4} \\

&=\quad nRT_H\ln\par{\frac{x_f\up{1}}{x_i\up{1}}}+nC_V(T_H-T_C)\\&\quad +\ \ \ nRT_C\ln\par{\frac{x_f\up{3}}{x_i\up{3}}}-nC_V(T_H-T_C) \\

&=nRT_H\ln\par{\frac{x_f\up{1}}{x_i\up{1}}}-nRT_C\ln\par{\frac{x_f\up{1}}{x_i\up{1}}} \\

&= (T_H-T_C)nR\ln\par{\frac{x_f\up{1}}{x_i\up{1}}} \\

&= (T_H-T_C)\D S\up{1} \\

&= E_\text{in} - E_\text{unused}\,,

\end{aligned}$$

where $\frac{x_f\up{3}}{x_i\up{3}} = \par{\frac{x_f\up{1}}{x_i\up{1}}}^{-1}$ was derived in phase 3 from the constraint that $\D S\up{1}=-\D S\up{3}$.

A good question to investigate is, why does the Carnot cycle produce net work? That is to say, why is $W_\text{out}$ not zero? Since phases 3 and 4 are the reversals of phases 1 and 2, it is surprising to me that there is some asymmetry between the joint process 1+2 vs 3+4. Clearly if we instead ran the phases in the order 1+2+4+3, the work of phases 1 and 2 would be undone (since 4+3 is the reverse of 1+2). I suspect the answer is that the mass function $m(x)$ is different in the compression and expansion phases, i.e. $\D m$ during expansion is greater than $\D m$ during compression. This is how we end up with less work extracted out of the piston on the way down (compression) than work done to the piston on the way up (expansion), leaving net energy in whatever the piston is acting on, i.e. net useful work done by the heat engine.

Regarding entropy, we know that the net change in entropy of the gas through the four phases is zero. However, there is a nonzero change in entropy in the environment during the cycle. In the previous section we showed that change in entropy of the reservoirs equals negative change in entropy of the gas (so that net entropy change is zero), i.e. $\D S_\text{hot} = -\D S\up{1}$ in phase 1 and $\D S_\text{cold} = -\D S\up{3} = \D S\up{1} = -\D S_\text{hot}$ in phase 3, where $\D S_\text{hot}$ and $\D S_\text{cold}$ are changes in entropy of the hot and cold reservoirs respectively. Thus, the hot reservoir loses $\D S\up{1}$ entropy units and the cold reservoir gains $\D S\up{1}$ entropy units, so we have a net transfer of $\D S\up{1}$ entropy units from the hot reservoir to the cold reservoir.

The efficiency of the Carnot cycle is

$$\eta=\frac{W_\text{out}}{E_\text{in}}=\frac{(T_H-T_C)\D S\up{1}}{T_H\D S\up{1}}=1-\frac{T_C}{T_H}\,.$$

Thus the greater the heat difference between source and sink, the more heat energy goes into net work on the piston.

Carnot’s big contribution is to prove that no process which uses a temperature difference between two heat reservoirs to move a piston can be more efficient than the Carnot cycle which does the same for a given $T_H$ and $T_C$. In general, a reversible process which performs some transformation is the most efficient possible process for that transformation. In practice, thermodynamic processes are irreversible due to unavoidable deviations from the ideal. These deviations usually take the form of irreversible heat loss due to friction or imperfect thermal isolation. For a real-world implementation of the Carnot cycle, if there is any energy leaving the combined process not accounted for by work done on the piston or heat moved to the sink, then the process will be less efficient than the ideal since then $E_\text{in} > W_\text{out} + E_\text{out}$, where $E_\text{out} = \abs{Q_C}$ is the recoverable energy dumped into the heat sink. Now in the irreversible case, $E_\text{unused} = E_\text{out} + E_\text{lost}$ where $E_\text{lost}$ is heat energy irreversibly lost to the environment.

Choosing the end of phase 1

I mentioned in #1 Isothermal expansion that the operator is free to choose the stopping point of phase 1: $x_f\up{1} > x_i\up{1}$. We saw above that $W_\text{out} = (T_H-T_C)nR\ln\par{\frac{x_f\up{1}}{x_i\up{1}}}$, and so the net work done on the piston is proportional to the log-ratio of initial to final container length, holding all else fixed. However, we also saw that the efficiency is $\eta=1-\frac{T_C}{T_H}$, which does not depend on $x_f\up{1}$, but only the heat ratio between the hot and cold reservoir that the Carnot cycle operates between. That implies that as $W_\text{out}$ increases, so does $E_\text{in}$ and $E_\text{out}$ to maintain the constant ratio $\eta = W_\text{out}/E_\text{in}$.

It would seem that the choice of $x_f\up{1}$ is then irrelevant, since whatever the value of $W_\text{out}$ is, the cycle can be repeated arbitrarily many times to extract the desired amount of work. Note that the bigger $x_f\up{1}$ is, the more time phase 1 takes.

A good question to investigate is whether there is any reason to prefer a shorter or longer phase 1. I suspect that choice might affect (1) the power of the Carnot cycle (i.e. work per time) and (2) the real-world inefficiency of any practical implementation of the Carnot cycle (a very long or very short phase 1 might suffer from too much friction or heat loss).

Irreversible Gas Transformations

In the discussion of the Carnot cycle above, we’ve defined two kinds of reversible transformations on a gas in a container: isothermal expansion/compression and isentropic expansion/compression. There are more such reversible processes on a gas, such as isobaric (constant pressure) and isochoric (constant volume). See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thermodynamic_cycle#A_list_of_thermodynamic_processes. There are many other sorts of ideal reversible cycles, such as the Rankine and Stirling cycles. See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thermodynamic_cycle#Well-known_thermodynamic_cycles.

However, we haven’t discussed what sorts of gas transformations are irreversible.

Standard irreversible gas transformations:

- Joule expansion (free expansion): The gas’s container suddenly increases in volume (e.g. a wall of the container is removed opening up the gas to another closed volume containing a vacuum). When the gas returns to equilibrium in the larger volume, we have an increase in entropy, $\D S = nR \ln\par{\frac{V_f}{V_i}}$, but without any reduction in entropy in the environment to compensate. There is no change in temperature of the gas because the gas is not pushing any movable wall, hence the expansion is “free” from resistance. We can think of this as slippage of the ideal counterpart: isentropic expansion.

- Heat transfer over a temperature difference (ref 1, ref 2): The gas’s container is put in thermal contact with another gas in a container at a different temperature. Both gas temperatures will converge to the same average temperature, but their combined entropy will go up. This is also slippage of an ideal counterpart: isentropic expansion/compression followed by an isothermal expansion/compression, so that the gas’s temperature is brought up/down to the temperature of the other gas before they are put into contact, and then the volume of the container is adjusted back while in contact with the other gas.

- Mixing two gasses: Two distinguishable gasses (different kinds of gas particles) initially in separate containers are allowed to mix in the combined volume by opening a wall between the two containers. This is a different sort of scenario than what we encountered in the Carnot cycle, but is a very interesting example of change in entropy. Neither the temperature or volume of the gasses changes, but their combined entropy goes up.

I mentioned earlier that expansion/compression of a thermally isolated gas need not be isenstropic (phases 2 and 4). In general, if the piston moves faster (in either direction) than the isentropic ideal, $nR \ln\par{\frac{V_f}{V_i}} = -nC_V\ln\par{\frac{T_f}{T_i}}$, then we have an irreversible transformation. When the container is expanding, $nR \ln\par{\frac{V_f}{V_i}}$ is positive. When the container is compressing, $nC_V\ln\par{\frac{T_f}{T_i}}$ is positive. If the container is expanded too vigorously, then $\abs{nR \ln\par{\frac{V_f}{V_i}}} > \abs{nC_V\ln\par{\frac{T_f}{T_i}}}$, and so $\D S > 0$. If the container is compressed too vigorously, $\abs{nC_V\ln\par{\frac{T_f}{T_i}}} > \abs{nR \ln\par{\frac{V_f}{V_i}}}$, and so also $\D S > 0$. Either way, the isentropic ideal, $\D S = 0$, is a lower bound on entropy change (I assume there is no way to reduce the entropy of an isolated gas).

Relationship between energy and entropy?

I don’t at the time of writing this understand the relationship between energy and entropy. I can surmise that the nature of that relationship is deep and fundamental, going well beyond the Carnot cycle. But the Carnot cycle let’s us pose a concrete instance of the question. However, I do caution drawing conclusions based only on the Carnot cycle, as it may not be representative of the general relationship between energy and entropy. As for myself, I see the Carnot cycle as a useful intuition pump for basic thermodynamic reasoning, but it needs to be complemented with other intuition pumps, ideally from non-equilibrium thermodynamics where many special case aspects of the Carnot cycle fall away.

One formulation of the question: Why is there not an ideal process that achieves maximum efficiency? That is to say, why does there need to be any unused energy, i.e. why $E_\text{unused} > 0$? Or posed another way, why cant the efficiency be 1.0 even in principle? Perhaps this question could be rephrased as, why does the efficiency of the Carnot cycle depend on the temperatures of the heat source and sink at all?

Another formulation: Why is there a necessary cost in the form of waste heat to convert heat into work? That is despite change in entropy across the entire system being zero. Conversely, why is there a necessary cost in the form of input work to move heat from cold to hot, despite change in entropy across the entire system being zero? Does moving energy around generally require additional energy cost? Or is it that moving energy from many degrees of freedom to fewer degrees of freedom requires additional energy cost?

Another line of questioning: Does decreasing the entropy of one system require some energy cost to be paid? Presumably, decreasing the entropy of one system requires the entropy of another system to increase so that total entropy does not decrease (2nd law), but moving entropy around like that also seems to require paying an energy cost. Why is that? What determines what energy cost needs to be paid for some transfer of entropy?