[This is an article, which is something I’ve optimized for readability and transmission of ideas, opposed to notes that are the seed of an idea and something I’ve written quickly.]

This is a long-winded attempt at formulating a question about thermodynamics. I will first give a high level #Overview of what this post is about, and then go through the technical details in the subsequent sections. Feel free to otherwise skip directly to #Part I Uncopying if you’d rather jump right in. The question is stated at the bottom: #Question.

$$

\newcommand{\D}{\Delta}

\newcommand{\set}[1]{\left\{#1\right\}}

\newcommand{\par}[1]{\left(#1\right)}

$$

Overview

Landauer’s principle is the conjecture that erasing physically stored data costs a minimum amount of energy, proportional to the number of bits being erased. Erasure here means subjecting the data storage medium (a physical system) to some process that maps all of its possible memory states to one single known state. For example, an array of computer bits might be mapped to the “all zero” state, 0000000… This process is performing a many-to-one mapping, i.e. many different physical states of the data storage medium have trajectories under this process that result in the same end state.

The known laws of physics obey time-symmetry, meaning that trajectories starting in different states don’t collide, i.e. given any current state, you can in principle determine what states the system occupied on any past or future time - at least given complete state information. To have a many-to-one process, the “which state” information being lost must actually have been moved somewhere else. In practice, when computer memory is reset, the information it had stored is dispersed into the environment. Landauer’s principle states that this dispersion necessarily accompanies a minimum amount of energy dispersion, which is the energy required to reset the bits. This dispersion is practically irreversible.

In general, thermodynamically irreversable processes, i.e. entropy increasing processes, have this same sort of many-to-one mapping that results in information loss (which is really information leakage).

This made me wonder whether it is possible to erase redundantly stored data without a thermodynamic cost. C. H. Bennett in his article, The thermodynamics of computation - a review (alt link), discusses situations when data redundancy can and cannot be reduced “for free”, as in, without an energy cost. He uses a toy system, called the Szilard engine, to construct an example where memory can be erased for free (no energy cost in the ideal limit). The Szilard engine runs repetitive cycles, just as the Carnot engine (a canonical thermodynamics example) runs repetitions of the Carnot cycle. So from here on I’ll refer to the Szilard cycle as the process being carried out in the Szilard engine.

The Szilard cycle extracts heat from a one-particle gas to do work on a piston. To do this, a bit of physical memory is used to store the outcome of a measurement. This thought experiment is useful for drilling down into some of the connections between thermodynamics reversibility and information.

In his article, Bennett shows that the process which performs the measurement and stores the outcome in a physical bit is, on its own, reversible. If that process is a copy operation, then its reverse is an uncopy operation, which puts the bit back in its known default state without energy cost (in the ideal setting). However, we cannot extract work from the one-particle gas if we uncopy the bit. The end of a full Szilard cycle results in the physical bit being cleared in the thermodynamically wasteful way that costs energy (at least as much energy as was extracted from the gas). Thus, we cannot extract free work from this gas, and the 2nd law of thermodynamics holds. It is only the memory erasing step which is irreversible (different from uncopying which is reversible).

However, I don’t see why the last step of the Szilard cycle cannot perform a different sort of uncopy process - one that is different from the copy process which wrote the bit, so that the work done by the gas is not undone. This appears to be a possibility because the information extracted from the gas into the bit is never lost during the Szilard cycle (see #Part II Information Is Never Lost), and so in principle, there is still redundant information between the gas and bit. Then for what reason can’t an uncopy be performed?

This post lays out the technical setup for my question in #Part I Uncopying and #Part II Information Is Never Lost. At the bottom I am able to pose this #Question rigorously. I don’t think I’ve discovered a loophole in the 2nd law. I fully expect that reversing the Szilard cycle is impossible, but I don’t understand why. I would love for someone to provide me an answer. I would find that very insightful and use it to improve my understanding of thermodynamics.

Part I: Uncopying

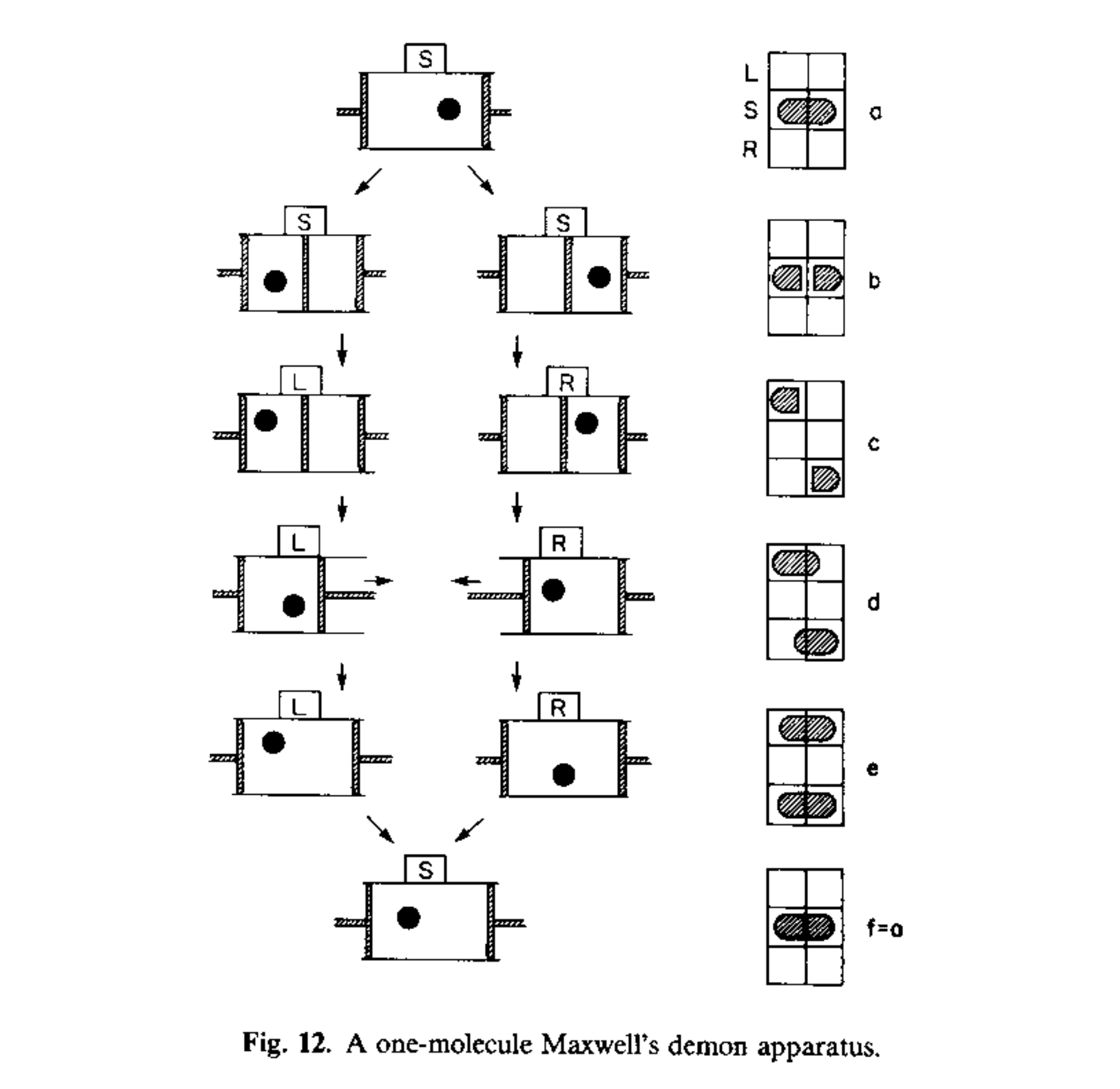

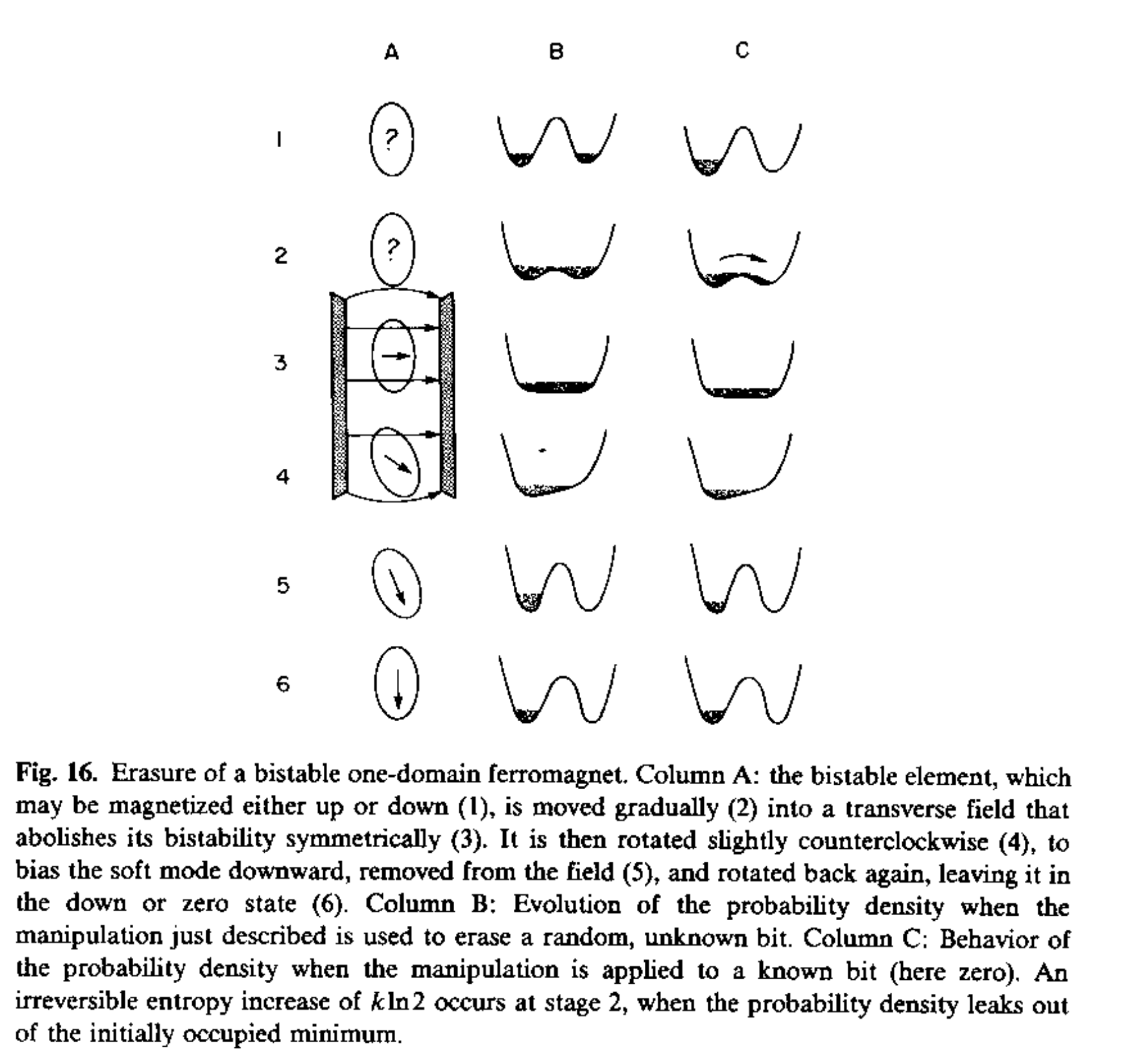

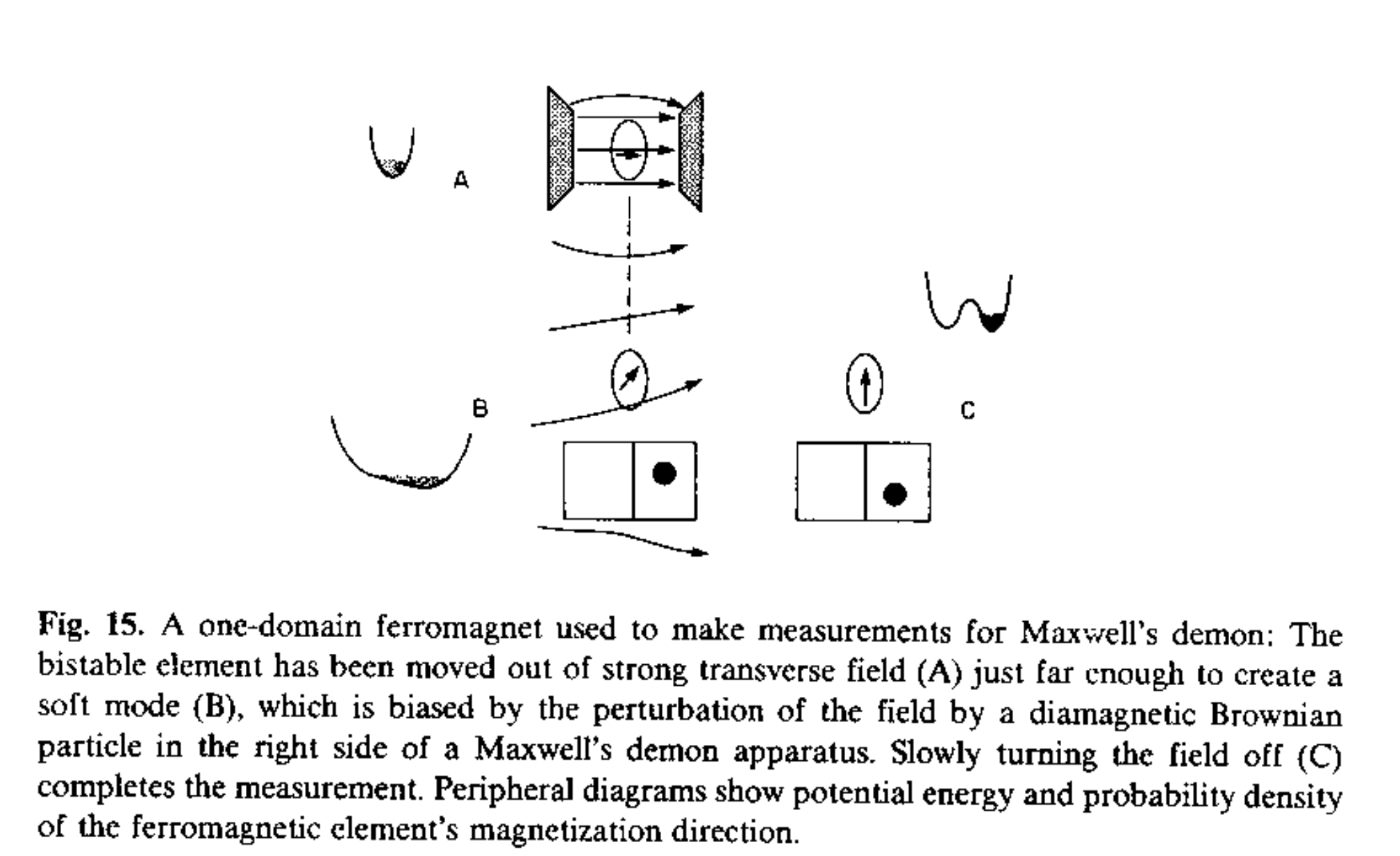

The following images are taken from C. H. Bennett’s article, The thermodynamics of computation - a review, section 5.

Szilard cycle

Szilard cycle

The Szilard cycle depicted above extracts kinetic energy (KE) from a particle in a box (which you could think of as a gas containing one particle) with unknown position and velocity, all the while without changing the size of the box on net (the start and end of the process have the same sized box).

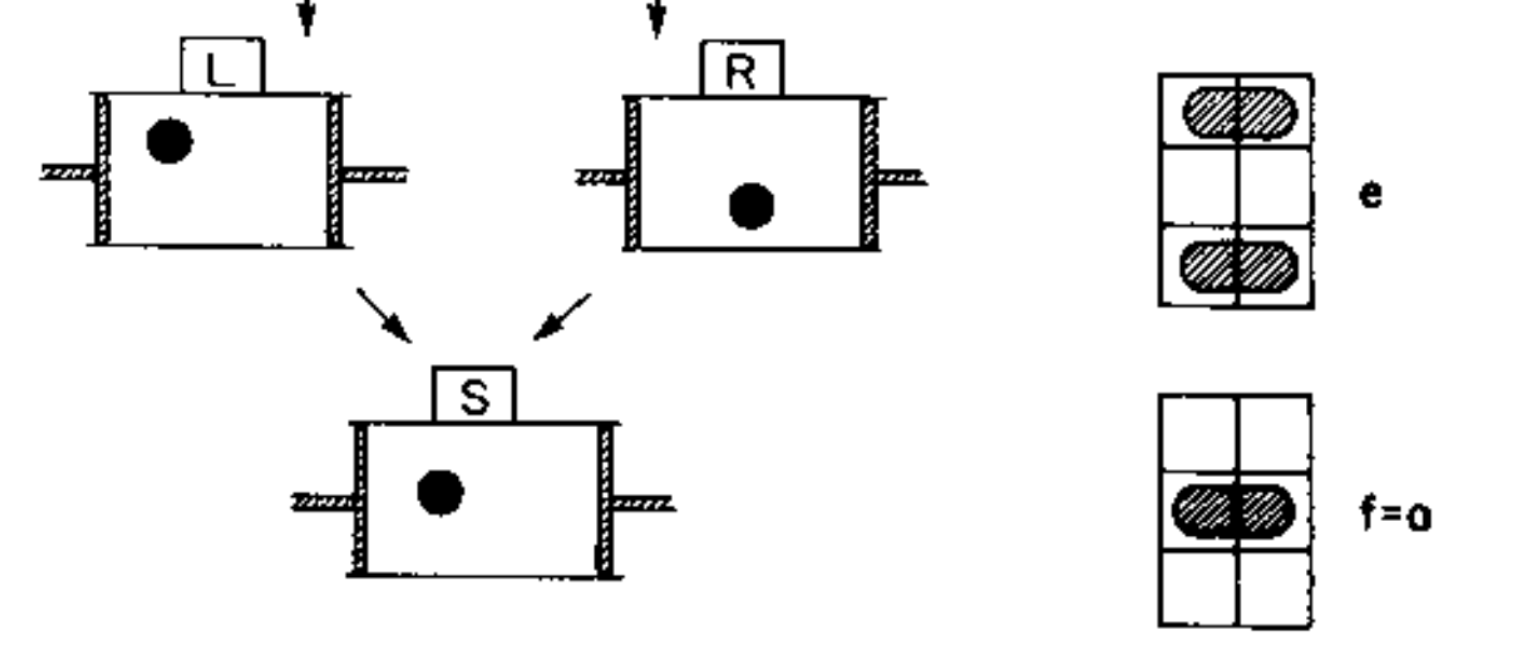

The steps of the Szilard cycle are:

(a)

The particle is initially somewhere in the box. The box has a piston on each end (a movable wall with resistance).

(b)

A barrier is placed that divides the box into two sections. We don’t know which section the particle occupies.

(c)

A measurement is taken which determines which section the particle is in. The measurement outcome is stored in a bit of physical memory depicted on the right. That bit is initialized in a known “standard” state S (what I previously called the default state). The measurement puts the bit into the left (L) or right (R) states, depending on which side of the box the particle occupies (from our perspective we don’t know which state the bit is in).

(d)

The which-side information, stored in our bit, is used to determine which piston to push towards the middle. If we push the piston into the particle we will transfer KE to it, thus costing us energy. We want to push the piston through a vacuum (the side without the particle), which is an energy-free operation (in the ideal limit). Then the barrier is removed. Whenever the particle collides with the piston, the piston will be pushed outwards toward the end of the box, but its resistance will cause the particle to lose some KE. The resistance is due to the piston being connected to something we care about transforming, e.g. like moving a mass up against gravity. In general, we say the piston is performing work, which is a useful application of energy.

(e)

The piston is pushed all the way to the end of the box until it cannot move any further, which is its initial state in step (a). The box is now returned to its initial state, and the particle is missing some KE which we converted into useful work. However, the bit of memory we used to store the which-side measurement still has that piece of information stored in it. The final step is to put the bit into the standard state S (erasure), bringing us to (f) and completing the cycle.

(f)

The physical memory is cleared (put back into the standard state S), and the cycle is complete. The only difference between (a) and (f) is the net KE extracted from the particle.

The Szilard cycle steps (a) through (e) are all reversible processes. That is to say, those steps can be undone without any energy cost. However, the memory erasure from step (e) to (f) is an irreversible process, since the information contained in the external memory is effectively lost when it is cleared. Landauer’s principle states that this irreversible erasure costs a minimum amount of energy, compensating for the apparent reduction in overall entropy of the particle-box system, thus preserving the 2nd law of thermodynamics, which states that the entropy of a system cannot be reduced for free. Step (f) makes the whole Szilard cycle irreversible.

Gas Thermodynamics

In classical thermodynamics, the change in entropy of a gas (with N particles) in a box, due to some process acting on the gas, is

$$

\D S = c_v\ln\frac{T_f}{T_i} + R\ln\frac{V_f}{V_i}

$$

where $c_v$ and $R$ are constants which depend on the kind of gas, $T_i$ and $T_f$ are respectively the initial and final temperature of the gas, and $V_i$ and $V_f$ are respectively the initial and final volumes of the gas (volumes of the box). Note that temperature and volume are equilibrium macrostates of the gas. They are not well defined when the gas is in a transitionary state, e.g. if it has uneven temperature or is not uniformly distributed across all of the free space in the box. Then the change in entropy of the gas is only well defined if the process starts and ends in equilibrium states where $T_i,T_f,V_i$ and $V_f$ are all well defined.

In some sense a one-particle gas is always in equlibrium. Its temperature is just the particle’s KE times a constant, (temperature is defined as being proportional to the average KE across all the particles) and its volume is just the volume of space the particle can access.

In the Szilard cycle, $V_i=V_f$, and $T_f = T_i - \frac{2}{3k}E$ where $E\geq0$ is the KE that was extracted from the particle and $k$ is the Boltzmann constant. Then the change in entropy from start to end of the cycle is proportional to $\ln\frac{T_f}{T_i}=\lg\par{1-\frac{2E}{3kT_i}} \leq 0$. The 2nd law of thermodynamics states that total entropy cannot decrease. Since we reduced the entropy of the gas, the entropy of some other system involved in the process must have gone up by at least the same amount. The entropy of the physical bit of memory is what must have increased.

Before the memory bit is erased, we can still reverse the process and move the entropy of the bit back into the gas (see #Uncopying). After the bit is erased, the entropy of the bit is moved into the environment, dispersed as heat energy. This is analogous to compressing an N particle gas to half of its volume, which heats up the gas enough to make the total change in entropy nonnegative, and then allowing the gas to cool down to its initial temperature by leaking heat into the environment. The gas compression and heating is reversible (an isentropic process; animation). What is irreversible is the loss of heat energy to the environment, just like our loss of our bit of information to the environment, which also implies a necessary loss of energy to the environment by Landauer’s principle.

Uncopying

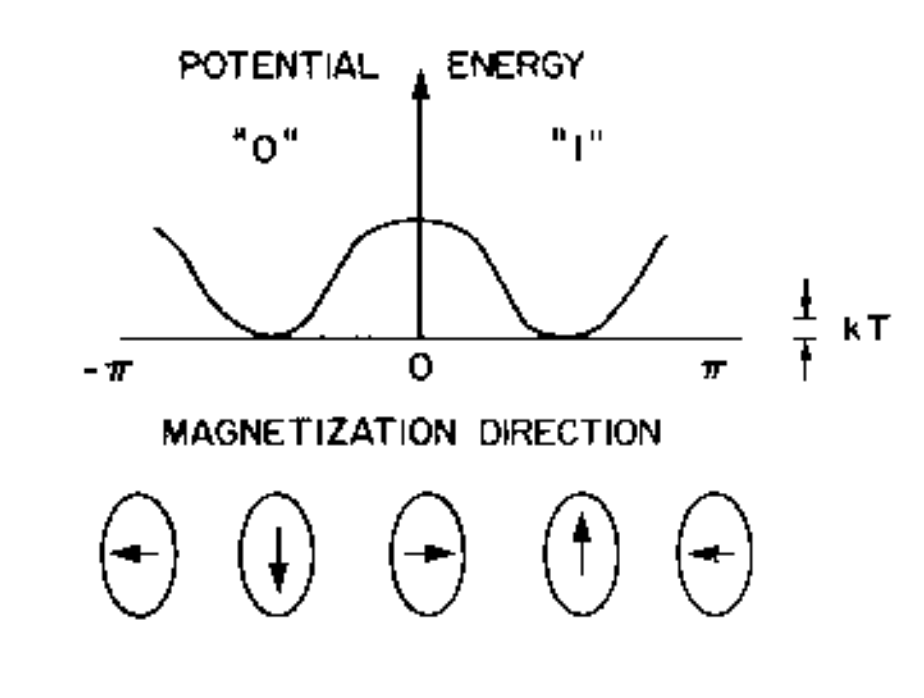

To serve as an intuition pump for how uncopying would work physically, Bennett uses a “one-domain ferromagnet”, which is a fancy way of saying an object with an intrinsic magnetic field (as opposed to electromagnet that requires an electric current) which is “simple” in its shape, specifically the magnetic field can be described by a single direction - an arrow oriented in space. I’ll refer to this object simply as “a magnet”.

Bennett supposes that absent any external magnetic fields, the magent’s field direction is stable, as in it is stuck in the up or down position. This can be represented by a potential field as a function of the magent’s angle of rotation:

Potential energy as a function of rotation angle. By default we assume there are two potential wells, centered around the up and down orientations. Getting over the diving hump requires some minimum amount of energy to be put into the magnet, in the form of angular momentum.

This magnet is our bit of physical memory. The magnet’s orientation stores a bit when it is in the up/down state, and is indeterminate when it has a sideways orientation.

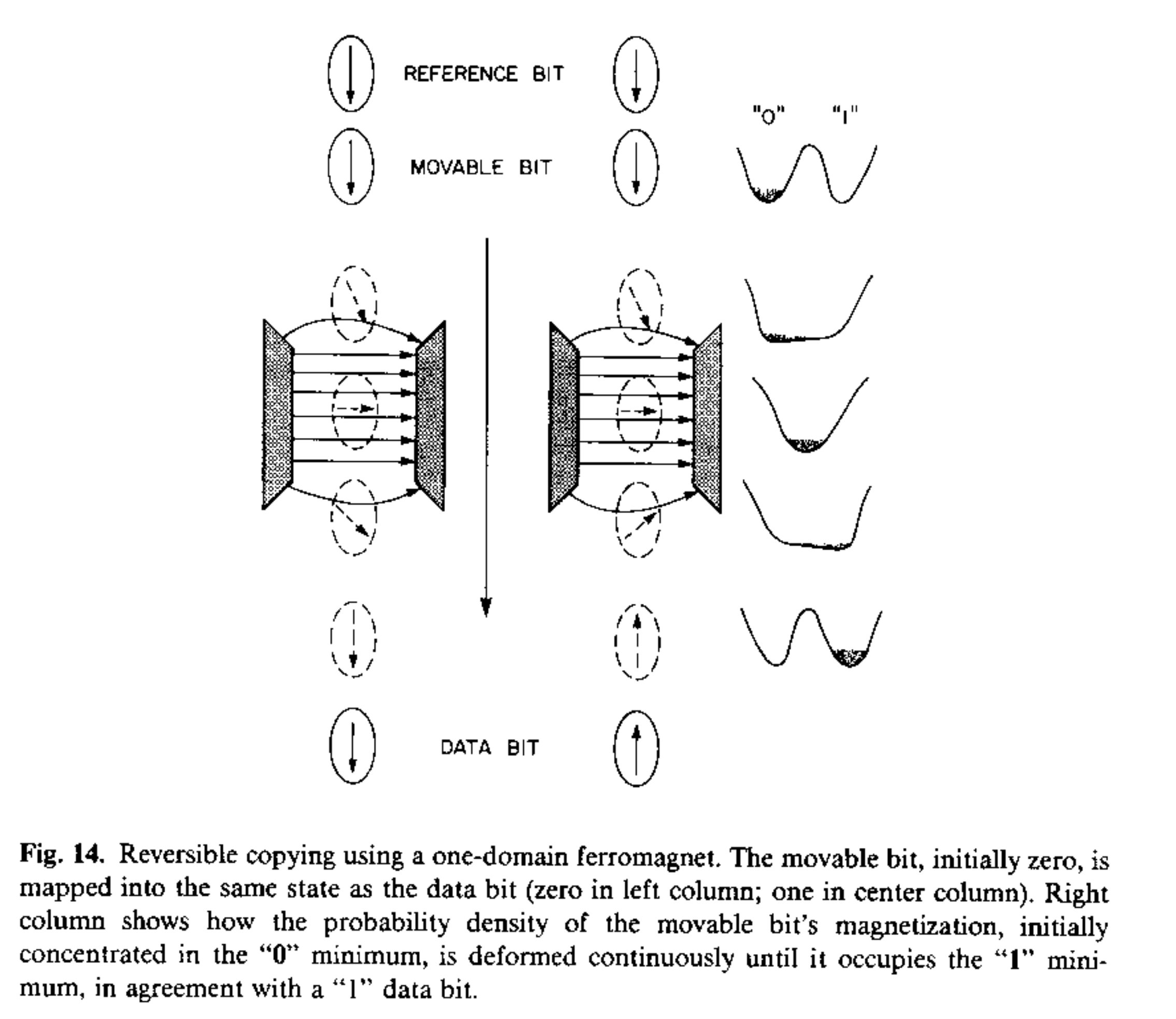

There is a simple process for copying the state of one magnetic bit onto another. In the figure below we have three magnets at play: the reference bit, the movable bit, and the data bit. The reference bit’s state is known to us, and defines what we consider to be the default (i.e. cleared, reset, erased) state of the bit we want to write to. The data bit contains information we want to copy to the movable bit.

The movable bit starts at the top nearby the reference bit. We require that the reference and movable bits start in the same orientation (otherwise we cannot perform this process “for free”). The diagram to the right depicts the region of state space (i.e. phase space) to which we know the movable bit occupies. Call this the state region of the movable bit (i.e. phase region).

We then push the movable bit downward through a sideways oriented magnetic field which has the effect of canceling out the magnetic field of the reference bit, causing the two potential wells to merge into one well. This transition from two to one well is smooth as the movable bit moves through the sideways magnetic field. As it moves further down towards the data bit, the single well morphs smoothly into two wells again.

Notice that during the transition the potential field from two to one wells, the field is is lopsided and asymmetric:

Likewise as the movable bit approaches the data bit, the potential field becomes lopsided again, which is how the movable bit “knows” which of the two wells to fall into as they emerge. The orientation of the data bit determines to which direction the movable bit will fall. Thus when the movable bit is close to the data bit, they are aligned and the copy is complete.

This copy process is entirely reversible. Its reverse process is called an “uncopy”, where the data bit (whose orientation is unknown to us) becomes the reference bit, and the reference bit (in the known default state) becomes the data bit.

Without the reference bit, the transition from two to one potential wells is symmetric, and the state region “spills over” the hump (timeline C below), causing our uncertainty about the magnet’s orientation to increase (corresponding to an entropy increase). This is an irreversible process.

Also, if the reference bit and movable bits start out with opposite orientations, then as the potential field becomes lopsided, it will raise up the potential well the movable bit is occupying (which is opposite the one the reference bit is occupying). Lifting up a potential field under an object implies transfer of energy to that object (as potential energy). That is to say, we spend energy moving the movable bit through the sideways magnetic field. On the other hand, when the movable bit is in the “correct” well to start with, the bottom of that well remains at the same potential level through out the copy process, just moving sideways to the center and then to which ever well the data bit occupies.

To perform the which-side measurement in the Szilard cycle, Bennett supposes the particle is charged so that the which-side information is naturally converted into magnetic orientation information. That is to say, the particle in a partition box is used as the data bit for our copy process. That copy process can be reversed with the uncopy process where the particle-box system becomes the reference bit. Note that the particle-box system is unaltered by the copy and uncopy operations.

Part II: Information Is Never Lost

(The following images and videos I made with Mathematica and Google Slides.)

The Szilard cycle is a deterministic process when modeled with classical mechanics (point particles following internal trajectories and colliding with rigid objects). Non-determinism enters the picture because we do not know the particle’s initial state. We can represent our uncertainty with the set of all initial states in which we think the particle might be, called a state region (usually “phase” region).

This is the partitioned box and its particle as depicted by Bennett in #Szilard cycle:

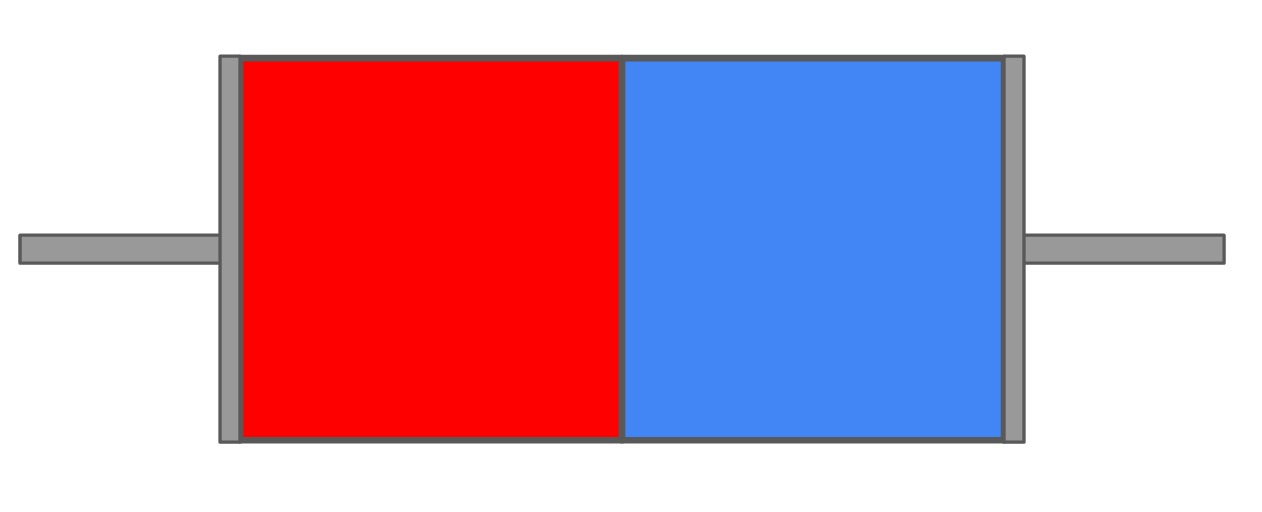

This is the same partitioned box with color-coded spatial regions which the particle could potentially be initialized to. Red is the left side and blue is the right side. Note that this depicts 2D space (as opposed to 2D state space below).

Here the which-side information is depicted with color: Initial states on the left are colored red and initial states on the right are colored blue.

However, this visualization leaves out a part of the state space: velocity. To be more precise, we should plot state space (phase space) which includes a velocity dimension for every position dimension. We would need a 4D plot for a particle in two spatial dimensions, and that is hard to visualize. For simplicity, let’s work with a particle confined to a single spatial dimension, giving us a 2D state space plot.

Here is shown all initial states (position and velocity) the particle could occupy. States are colored red or blue for the left and right sides of the box respectively. Phase space plot of the initial state regions, separating out positive (rightward) and negative (leftward) velocities onto the positive and negative sides of the velocity axis (vertical). This depicted state region implies we know the particle’s velocity magnitude is within a certain range.

For simplicity, I will model the piston pushing phase (d) from the Szilard cycle as a single continuous process. That is to say, instead of having the particle bounce off the piston many times, moving it slightly in discrete jumps, I will model the collision of the particle with the piston as fully inelastic, i.e. the particle and piston stick together and move together until the piston has reached the end of the box, at which point the particle bounces off. The particle gradually loses KE and slows down as it moves with the piston.

For example, the trajectory of a particle initialized on the right side with a rightward facing velocity:

The trajectory of a particle initialized on the right side with a leftward facing velocity:

To show how the initial state regions (left and right sides) evolve over time, I uniformly sampled an ensemble of initial particle states and animated their trajectories over time:

It is clear from this animation that none of the trajectories overlap at any point. That means, in principle, one could determine which side the particle started in at any point in time if they could measure which color region the particle is currently in. The red and blue regions become more mixed over time, but they are always disjoint.

Here at a later point in time the red and blue regions are still interlaced in a striped pattern:

Question

Is it possible to use the scrambled which-side information (striped red-blue pattern above) contained in step (e) of the #Szilard cycle to induce a reference magnetic field for an uncopy process? That would allow us to uncopy the bit of memory in the Szilard cycle without undoing the work we extracted from the particle.

The specific modification to the Szilard cycle I’m proposing is this: Step (f) irreversibly resets the memory bit, costing some minimum amount of energy. Instead, consider an alternative step (f') where the external memory is reset back to the standard (default) state S via an uncopy process - the reversal of the copy process. As we saw above, this can be done without energy cost. The Szilard cycle with step (f') replacing step (f) would be reversible throughout, seemingly violating the 2nd law because total entropy would have decreased (it is not obvious to me that this uncopying would result in an increase in entropy anywhere else).

It is safe to assume the 2nd law does hold. The question then becomes, what prevents us from using the scrambled which-side information in the “gas” to uncopy the memory bit? Is this operation fundamentally disallowed by physics for whatever reason? Or is it merely a matter of technologically intractability? For instance, as time progresses the interlacing of red and blue becomes finer and finer, requiring finer and finer device precision.

We could tackle this question by asking instead, is it possible to perform an observation on the particle such that only its “color” (which side it came from) is recorded in one bit of memory? If so, then the reverse of this process is the uncopy operation we are seeking. We already know that we could measure the particle’s position and velocity precisely (assuming a classical particle) using, say, a camera. The “camera process” would write many bits to memory (including a lot more than the particle’s state). Note that we would need to take two pictures in quick succession to capture the particles velocity. To reverse THAT process, we would need to feed as input ALL of the bits of information the camera would output in the forward direction. Without that input information, we cannot uncopy just a single bit, even if its a subset of the information.

Thus, the question becomes, can we create a process that converts only the particle’s “color” information into magnetic polarity for use in an uncopy process? If no such process exists, how would we prove it?